#47: Introducing a Fictional Setting Through Movement and Attention

Scott Lynch, Rebecca Roanhorse, Colson Whitehead, J.R.R. Tolkien, Sofia Samatar, Erika Swyler

Hello friends, and Happy New Year! A quick bit of housekeeping before I dive into this month’s essay: after a couple years of choosing not to do this, I’m turning on paid subscriptions, partly because people keep kindly pledging their support. (Thank you!) Other than that option being available if you’d like, nothing else should change at present. Sometime in the future—especially once some of these essays begin to form a follow-up to Refuse to Be Done—I may paywall the archives, but the newest essay will always be free. That said, if enough people subscribe, I’ll also start doing some kind of subscriber-only second newsletter each month, perhaps answering craft questions from paying subscribers or something similar. (Feel free to let me know if something like that would be of interest to you.)

Thanks in advance to everyone who has already pledged a paid subscription, and to anyone who does so in the future. I’m hoping to use whatever earnings come in to defray some necessary research travel for my next novel, so know that if you do choose to pay, your kindness will get rolled right back into more of my writing.

Okay! With our commerce out of the way, let’s move on to this month’s craft essay!

In writing invented worlds—or any setting likely to be unfamiliar to the majority of your intended readers—there are at least two problems we need to solve for the reader, as efficiently as possible: 1) What is the world of the story like? What is its geography, its features, its pleasures and its dangers? What do the characters see and hear and smell, and how does that differ from the world we know? 2) Why should the reader care about what happens to this invented place?

I could go on about both topics at length, but today I want to focus on the first. (If nothing else, it’s more easily done than the second: establishing meaningful secondary world stakes can be a job.) How do we introduce readers to a fantastical or science-fictional setting without infodumps and expositional overload?

One frequently successful tactic is to move the protagonist or point-of-view character through a tour of the setting, in a scene with clear purpose and urgency, all the while showing the setting through the character’s eyes, not the writer’s. Why does this matter? Because, while the reader may or may not care about what the writer cares about, they will care about whatever the protagonist gives their attention to—because it’s the protagonist the reader is usually meant to identify with, not the writer.

Let’s look at a couple examples I find particularly successful. Apologies in advance for the long block quotes: this is one of those literary effects that’s harder to explore using only brief bits.

First up is Rebecca Roanhorse’s Black Sun, where we initially explore the capital city Tova—the center of an invented fantastical setting based on pre-Columbian Native American and Mesoamerican cultures—through the eyes of Naranpa, the Sun-Priest leader of Tova’s Watchers of the Celestial Tower, who’s about to lead a procession through the city: “Naranpa had forced the priesthood to gather at the foot of the bridge to Odo at sunrise,” Roanhorse writes, “and no one was happy about it.” As the parade begins, she continues:

The four priests walked in a horizontal line behind the drum and smoke with their dedicants, counting forty-eight for each, trailing in single-file lines behind them like the tails of falling stars.

As they crossed the bridge into Odo, Naranpa marveled at the view of her beloved city. Tova at dawn was always a sight to behold. Its sheer cliffs were wreathed in mist and its famed woven bridges blanketed in frost, the dawn light making everything glow, ethereal and otherworldly. Behind her she knew the celestial tower stood, ever vigilant, its six stories rising from a small freestanding mesa separated from the rest of the city by bridges. In it lived the priests, dedicants, and a small contingent of live-in servants. It also included a library of maps and paper scrolls, a terrace where they all ate meals together, and, on the rooftop, a large circular observatory open to the night sky.

Home, she thought. A home she loved, even if she wasn’t always sure she belonged. But that was the Maw talking, making her feel unworthy. The voice in her head that reminded her that she was the only Sun Priest in recorded memory who was not from a Sky Made clan.

Naranpa holds a contradiction at the center of her person, one that informs how she sees Tova: she’s both the highest-rank priest and is descended from the city’s lowest social class. This informs everything she does, including what she notices in the setting and her awareness of the other clans and their relative rankings. As we read on, she pauses to help one of her dedicants cross the swaying bridges between Sky Rock and Odo, their next destination, rich with history Naranpa knows well:

The bridge deposited them two stories down from the main throughway, and they had to walk up a flight of narrow and well-worn stone stairs to reach the district proper. Once they reached the top, the home of Carrion Crow stood before them. The district was known for the soft volcanic rock from which its earliest homes had been built. When Carrion Crow first claimed the high cliffs, the buildings had been carved into the original walls, and here and there as they walked down the main road, Naranpa still caught sight of these ancient structures hiding down the side alleys or slipped between more recent buildings. Most homes now were made from irregular bricks quarried and fashioned from the same type of volcanic rock but brought in from outside of Tova. And homes now were finished with wood, either charred to match the black bricks or, on more expensive homes and shop fronts, painted a bright crimson red. And everywhere the crow motif, the distinctive crow skull, was woven on the banners hung from walls and carved into the lintels over doorways.

“Black buildings and black looks,” one of the other high priests murmurs, as they pass through. “It does not bode well to start our day.”

The procession continues throughout the chapter, introducing the reader not only to the various districts of the city, but also—crucially!—how Naranpa and the other priests feel about the people who populate them. They pass out of Odo and into Kun, where the Winged Serpent Clan lives, and then onward in a loop around the city, as Naranpa explains to the others: “We’ll cross the Tovasheh to Titidi by way of Sun Rock. Then we can walk Titidi and Tsay and back across to Otsa by Sunset.”

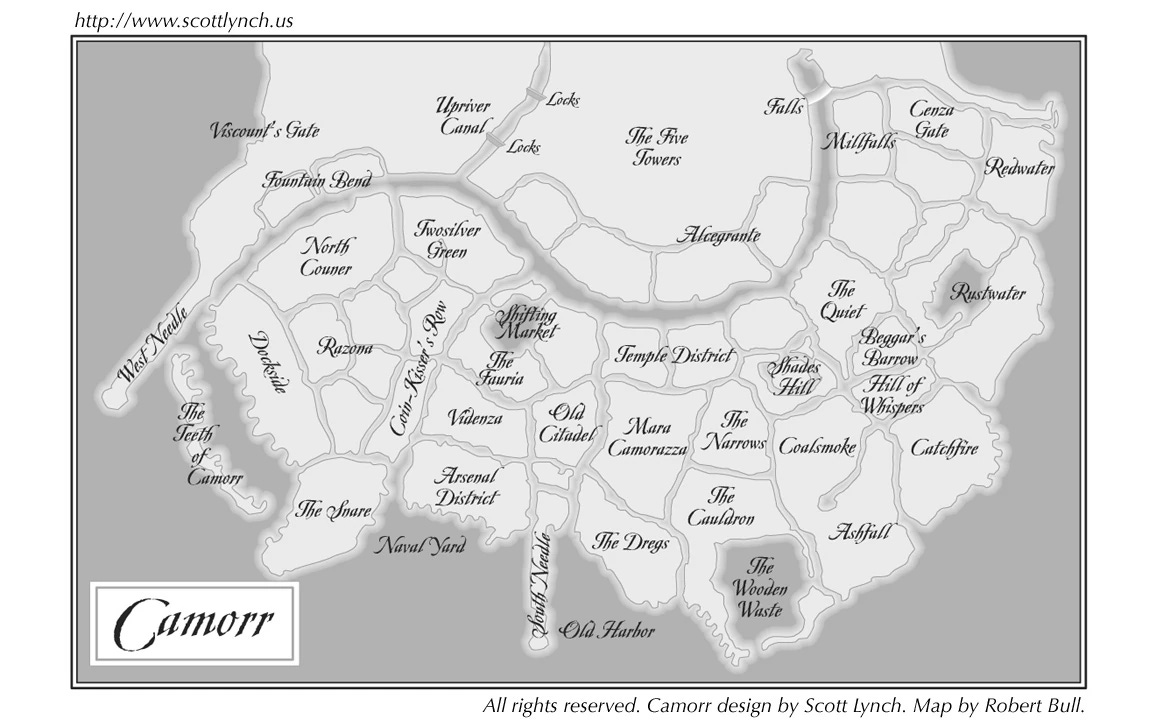

Or so the plan goes—but trouble arrives before the procession can finish its loop, with a deadly attack cutting their journey short on the passage across Sun Rock and kicking the novel’s plot into gear. By the time this inciting incident happens, Roanhorse’s parade has served its purpose, introducing the reader to the novel’s central city and to the politics of the people who inhabit it, as well as the important historical events whose aftershocks will resonate through the novel. A quick glance at the novel’s endpaper map allows a reader to scan the parade path, and to start to put these invented places into relation with each other:

Crucially, what animates this tour of Tova—what keeps it from being an expositional infodump—is Naranpa’s perspective, which enlivens everything we encounter. Again, the reader will care about anything the characters care about—which means anything we see through their embodied perception, instead of in distant omniscient or otherwise detached narration. This parade is Naranpa’s idea, which means the trouble that eventually cuts it short is her trouble too—and so doesn’t it follow that she has to become the hero of this story, striving to save both herself and her city?

In Scott Lynch’s The Lies of Locke Lamora, the title character is the leader of a band of thieves called the Gentlemen Bastards, who steal from the rich in the vein of Robin Hood, but without his giving to the poor. The novel proper opens with Lamora and his gang aiming to pull off a confidence game to defraud a local noble, a plot that requires a watery entry and escape on the canals of the city of Camorr, a city perhaps inspired by our Venice. Many of the novel’s first pages are dedicated to the gang being piloted through the city canals by Bug, the group’s youngest member:

Bug had poled himself, Locke, and Jean from the Via Camorrazza into the Shifting Market right on schedule, just as the vast Elderglass wind chime atop Westwatch was unlashed to catch the breeze blowing in from the sea and ring out the eleventh hour of the morning.

The Shifting Market was a lake of relatively placid water at the very heart of Camorr, perhaps half a mile in circumference, protected from the rushing flow of the Angevine and the surrounding canals by a series of stone breakwaters. The only real current in the market was human-made, as hundreds upon hundreds of floating merchants slowly and warily followed one another counterclockwise in their boats, jostling for prized positions against the flat-topped breakwaters, which were crowded with buyers and sightseers on foot.

City watchmen in their mustard-yellow tabards commanded sleek black cutters—each rowed by a dozen shackled prisoners from the Palace of Patience—using long poles and harsh language to maintain several rough channels through the drifting chaos of the market. Through these channels passed the pleasure barges of the nobility, and heavily laden freight barges, and empty ones like that containing the three Gentlemen Bastards, who shopped with their eyes as they sliced through a sea of hope and avarice.

In just a few lengths of Bug’s poling, they passed a family of trinket dealers in ill-kept brown cockleshells, a spice merchant with his wares on a triangular rack in the middle of an awkward circular raft of the sort called a vertola, and a Canal Tree bobbing and swaying on the leather-bladder pontoon raft that supported its roots. These roots trailed in the water, drinking up the piss and effluvia of the busy city; the canopy of rustling emerald leaves cast thousands of punctuated shadows down on the Gentlemen Bastards as they passed, along with the perfume of citrus. The tree (an alchemical hybrid that grew both limes and lemons) was tended by a middle-aged woman and three small children, who scuttled around in the branches throwing down fruit in response to orders from passing boats.

Above the watercraft of the Shifting Market rose a field of flags and pennants and billowing silk standards, all competing through gaudy colors and symbols to impress their messages on watchful buyers. There were flags adorned with the crude outlines of fish or fowl or both; flags adorned with ale mugs and wine bottles and loaves of bread, boots and trousers and threaded tailors’ needles, fruits and kitchen instruments and carpenters’ tools and a hundred other goods and services. Here and there, small clusters of chicken-flagged boats or shoe-flagged rafts were locked in close combat, their owners loudly proclaiming the superiority of their respective goods or inferring the bastardy of one another’s children, while the watch-boats stood off at a mindful distance, in case anyone should sink or commence a boarding action.

Up to this point, no one has spoken, and so the narration remains at a remove, not necessarily attached to any particular consciousness, as Roanhorse’s was attached to Naranpa. But The Lies of Locke Lamora is written in an omniscient POV, allowing for a changeable narrative distance, and for dipping into multiple characters’ individual consciousnesses in the same scene. We can see this begin once dialogue appears:

“It’s a pain sometimes, this pretending to be poor.” Locke gazed around in reverie, the sort Bug would have been indulging in if the boy hadn’t been concentrating on avoiding collision. A barge packed with dozens of yowling housecats in wooden slat cages cut their wake, flagged with a blue pennant on which an artfully rendered dead mouse bled rich scarlet threads through a gaping hole in its throat. “There’s just something about this place. I could almost convince myself that I really did have a pressing need for a pound of fish, some bowstrings, old shoes, and a new shovel.”

“Fortunately for our credibility,” said Jean, “we’re coming up on the next major landmark on our way to a fat pile of Don Salvara’s money.” He pointed past the northeastern breakwater of the market, beyond which a row of prosperous-looking waterfront inns and taverns stood between the market and the Temple District.

“Right as always, Jean. Greed before imagination. Keep us on track.” Locke added an enthusiastic but superfluous finger to the direction Jean was already pointing. “Bug! Get us out onto the river, then veer right. One of the twins is going to be waiting for us at the Tumblehome, third inn down on the south bank.”

Bug pushed them north, straining to reach the bottom of the market’s basin—which was easily half again as deep as the surrounding canals—with each thrust. They evaded overzealous purveyors of grapefruits and sausage rolls and alchemical light-sticks, and Locke and Jean amused themselves with a favorite game, trying to spot the little pickpockets among the crowds on the breakwaters. The inattention of Camorr’s busy thousands still managed to feed the doddering old Thiefmaker in his dank warren under Shades’ Hill, nearly twenty years since Locke or Jean had last set foot inside the place.

As the narrative distance collapses toward to our characters, details become specific to what they would each notice: Jean points out the richer districts ahead, where their wealthy quarry waits; Locke and Jean use their particular expertise and history as thieves to suss out the child pickpockets in the distant crowd. These details emerge from the forms of attention of these particular characters, and it’s by their presence that we come to know not only our setting but our group of heroes.

Next, let’s look at an example from a realist novel that uses more or less the same tactics as the two fantasy novels above, to solve a similar problem: how can we bring the reader into an unfamiliar setting that most of us (hopefully, in this case) have no familiarity with? In Colson Whitehead’s The Nickel Boys, Elwood, who had been bound for college before unjustly running afoul of the law, and his new companion Franklin arrive together at the Nickel Academy, an infamous (and too often deadly) reform school. The following is from the chapter where Elwood is transported to Nickel, along with several other boys and young men:

Outside of Gainesville they drifted off the interstate. The officer pulled over to let everyone piss and gave them mustard sandwiches. He didn’t cuff them when they got back in the car. The officer said he knew they weren’t going to run. He skirted Tallahassee, taking the back road around it like the place didn’t exist anymore. I don’t even recognize the trees, Elwood told himself when they got to Jackson County. Feeling low.

I don’t even recognize the trees, Elwood thinks, and why should he? He’s passed out of the life he’s known into somewhere else, somewhere foreign and fraught. But for a moment, he lets himself believe things might not be as bad as he initially worried:

He got a look at the school and thought maybe Franklin was right—Nickel wasn’t that bad. He expected tall stone walls and barbed wire, but there were no walls at all. The campus was kept up meticulously, a bounty of lush green dotted with two- and three-story buildings of red brick. The cedar trees and beeches cut out portions of shade, tall and ancient. It was the nicest-looking property Elwood had ever seen—a real school, a good one, not the forbidding reformatory he’d conjured the last few weeks. In a sad joke, it intersected with his visions of Melvin Griggs Technical, minus a few statues and columns.

They drove up the long road to the main administration building and Elwood caught sight of a football field where some boys scrimmaged and yelped. In his head he’d seen kids attached to balls and chains, something out of cartoons, but these fellows were having a swell time out there, thundering around the grass.

“All right,” Bill said, pleased. Elwood was not the only one reassured.

The officer said, “Don’t get smart. If the housemen don’t run you down, and the swamp don’t suck you up—”

“They call in those dogs from the state penitentiary, Apalachee,” Franklin said.

“You get along and you’ll get along,” the officer said.

Once again, Elwood is trying to reassure himself that maybe his time at Nickel won’t be so bad. It was the nicest-looking property Elwood had ever seen. It reminds him of the college he’d planned to attend. There are boys playing football. And yet—doesn’t he hear the threat of the housemen, the swamps, the prison dogs? If so, he doesn’t focus on it—yet.

Inside the building the officer waved down a secretary who took them into a yellow room whose walls were lined with wooden filing cabinets. The chairs were in classroom rows and the boys picked spots far apart from one another. Elwood took a place in the front, per his custom. They all sat up when Superintendent Spencer knocked the door open.

Spencer nodded at Franklin, who grabbed the corners of his desk. The supervisor suppressed a smile, as if he’d known the boy would be back. He leaned against the blackboard and crossed his arms. “You got here late in the day,” he said, “so I won’t go on too long. Everybody’s here because they haven’t figured out how to be around decent people. That’s okay. This is a school, and we’re teachers. We’re going to teach you how to do things like everyone else.

“I know you heard all this before, Franklin, but it didn’t take, obviously. Maybe this time it will. Right now, all of you are Grubs. We have four ranks of behavior here—start as a Grub, work your way up to Explorer, then Pioneer, and finally, Ace. Earn merits for acting right, and you move on up the ladder. You work on achieving the highest rank of Ace and then you graduate and go home to your families.” He paused. “If they’ll have you, but that’s between y’all.” An Ace, he said, listens to the housemen and his house father, does his work without shirking and malingering, and applies himself to his studies. An Ace does not roughhouse, he does not cuss, he does not blaspheme or carry on. He works to reform himself, from sunrise to sunset. “It’s up to you how much time you spend with us,” Spencer said. “We don’t mess around with idiots here. If you mess up, we have a place for you, and you will not like it. I’ll see to it personally.”

Spencer had a severe face, but when he touched the enormous key ring on his belt the corners of his mouth twitched in pleasure, it seemed, or to signal a murkier emotion. The supervisor turned to Franklin, the boy who’d come back for a second taste of Nickel. “Tell them, Franklin.”

Franklin’s voice cracked and he had to fix himself before he got out, “Yes, sir. You don’t want to step over the line in here.”

Franklin knows what Elwood doesn’t know, or doesn’t want to know, but that the reader knows too, because Whitehead has already shown us the future of this place in the prologue: The Nickel School is an evil place—or, more accurately, a place where evil is done—and not every boy who comes there survives his stay. Here, Elwood’s optimism shields him from the reality of some of what he sees, as he self-selects to focus on details that paint a rosier picture than the scene would if it was from Franklin’s point of view—or, for that matter, from Whitehead’s, or mine, as an attentive reader. This time, it’s the gap between the accuracy of Elwood’s consciousness moving through this space and ours following him that produces much of the scene’s tension, all the while foreshadowing the horrors to come.

Finally, in the interest of fairness, here’s one example of what happens when the narrative distance is kept maximal and the prose isn’t attached to any particular character’s consciousness. What we have instead is full storyteller voice, with a narrator speaking directly to the reader without worrying about the artifice of doing so, and setting the scene according to his own interests:

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort.

It had a perfectly round door like a porthole, painted green, with a shiny yellow brass knob in the exact middle. The door opened on to a tube-shaped hall like a tunnel: a very comfortable tunnel without smoke, with panelled walls, and floors tiled and carpeted, provided with polished chairs, and lots and lots of pegs for hats and coats—the hobbit was fond of visitors. The tunnel wound on and on, going fairly but not quite straight into the side of the hill—The Hill, as all the people for many miles round called it—and many little round doors opened out of it, first on one side and then on another. No going upstairs for the hobbit: bedrooms, bathrooms, cellars, pantries (lots of these), wardrobes (he had whole rooms devoted to clothes), kitchens, dining-rooms, all were on the same floor, and indeed on the same passage. The best rooms were all on the left-hand side (going in), for these were the only ones to have windows, deep-set round windows looking over his garden, and meadows beyond, sloping down to the river.

If a character’s attention moving through space is one way to help introduce a setting and make it meaningful to a reader, it’s certainly not the only way. After all, how many of us have long dreamed of a hobbit hole all our own, a want that was perhaps seeded not with character but by this description on the first page of Tolkien’s The Hobbit, offered up several paragraphs before we ever see our dear Mr. Baggins in scene?

What I’m Reading:

Opacities by Sofia Samatar. A great book on the writing life, and maybe especially the mid-career writing life, where one tries to get back to the essentials of what made them want to write in the first place. It’s absolutely beautiful, so smart, and it made me want to immediately go write and otherwise make art, which is exactly what a book on writing should do. “I wanted to send you something very small and perfect that would say everything,” Samatar writes. “A single sentence. A word. A letter.”

We Lived on the Horizon by Erika Swyler. Out this week, Swyler’s latest is not just my favorite of her books, but one of my favorite sci-fi novels of recent years. I had the pleasure of reading it last year in order to blurb it, and here’s what I wrote: "Erika Swyler's We Lived on the Horizon delivers everything I crave from great science fiction: a pulse-quickening plot, an endless stream of imaginative wonders, and the kind of moral clarity that brings to mind the grand ethical visions of writers like Ursula K. Le Guin and Iain M. Banks. This is an unforgettable novel of ideas, keen to the complex interplays between love and sacrifice, complicity and community." Don’t miss this one.

Thanks so much for reading! If you’re not already subscribed, please consider doing so by clicking the button below.

Matt Bell’s novel Appleseed (a New York Times Notable book) was published by HarperCollins in July 2021. His craft book Refuse to Be Done, a guide to novel writing, rewriting, & revision, is out now from Soho Press. He’s also the author of the novels Scrapper and In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods, as well as the short story collection A Tree or a Person or a Wall, a non-fiction book about the classic video game Baldur’s Gate II, and several other titles. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Esquire, Tin House, Conjunctions, Fairy Tale Review, American Short Fiction, and many other publications. A native of Michigan, he teaches creative writing at Arizona State University.

The opening of Hamnet is a great example of describing the world and setting up the book’s stakes and themes. It’s a boy looking for his family in their empty house—we readers (most likely) know what is going to happen to the boy, so it’s moving to be introduced to the world through his eyes.

Terrific. Thanks!