#52: How I Research a Novel, in the Stacks and in the World

Andrea Barrett, Allison Amend, Lauren Groff, Will Chancellor

Hello friends,

Later this week, I’m leaving on a month-long trip to Europe, spending two weeks or so trekking solo on a pilgrimage in Spain before meeting my partner in Geneva to travel on to the Alps to hike the Tour du Mont Blanc. The solo phase of the trip is mostly novel research and the second mostly vacation but I expect some useful overlap across the two adventures, in part because so much of what I’m writing about these days (across multiple projects) concerns long-distance overland travel in one way or another. If all goes well, I’ll cover three hundred-plus miles on foot across four countries in thirty days, and I hope the experiences I have along the way will be useful when I get back to the desk.

For me, getting to conduct research both in-person and in libraries and other archives is one of the best reasons to be a writer. I’ve always wanted to tell stories, but I’ve also come to consider novel writing my preferred form of inquiry, a mode of exploring not just my place in the world but also history, science, ethics, and other areas of thought. I’m not really a trained scholar but writing novels allow me to moonlight as one for a while, dipping in and out of dozens of disciplines and subject areas over the course of writing a book. More often than not, this research is a delight, allowing me to chase old obsessions and develop new ones.

Ideally, following such obsessions eventually results in a finished novel or story, but sometimes the research remains enjoyable or useful even after the related project fails. About ten years ago, I spent a year and a half writing and researching a novel that I ultimately put aside not because the novel wasn’t working but because the research convinced me I was so out of my depths that there probably wasn’t an ethical way to write the book I’d intended. (At least not for me, at that time.) But that research changed my worldview on certain topics forever, and so I treasure that “failure” too.

Obviously there’s no one right way to do research, and different projects can demand wildly different amounts of investigation. But almost everything I write these days requires at least some, and I imagine almost any story or novel can benefit from it, even if it begins from the writer’s direct lived experience or preexisting area of expertise. In any case, here’s how I go about my research, in hopes that my approach might help you with yours.

Read, Read, Read

There’s a bookshelf next to my desk that I empty each time I start a new novel. As I write, I research, and as I research, I slowly fill this shelf with fiction and poetry, reference texts, academic books, popular nonfiction about various topics, art and architecture books, maps, travel guides, and all manner of other texts and objects. To give an example of the range, here’s a sampling of the areas I read in while writing my last novel Appleseed:

Science fiction, eventually focusing on novels of ideas and anthropological or social sci-fi (Ursula K. Le Guin, Iain M. Banks, many others)

Environmental essays/journalism (Wendell Berry, Annie Dillard, Paul Kingsnorth, Elizabeth Kolbert, Robin Wall Kimmerer, Robert Macfarlane, and more)

Environmental philosophy (Timothy Morton, Amitav Ghosh, Anna Tsing, Roy Scranton, Donna Haraway, etc.)

Scientific research into cloning, gene splicing, geoengineering, automation, industrial food systems, rewilding, nuclear waste management, communications with distant futures

Historical period research (settler colonialism, Manifest Destiny, the domestication of the apple, histories of the Midwest, etc.)

Myth, religion, and folk tales (Johnny Appleseed, Orpheus and Eurydice, the Fates and the Furies, the Book of Genesis)

To write my one book, I read a couple hundred others. That’s not a very efficient input/output ratio, I’ll admit, but I enjoyed so much of the reading that it usually wasn’t exactly work. (Which isn’t to say that some of my self-assigned “required” reading wasn’t a slog! But sometimes the slog gives up a gem, so…)

In Dust and Light, her book on “the art of fact in fiction,” Andrea Barrett relates a similar experience had while researching her story “Two Rivers”:

“Two Rivers” began with a long wade through the history of utopian communities, which set me to investigating the many early American naturalists who’d been involved with New Harmony and then to a crucial moment in the history of paleontology. As that story grew, I learned about the physical and economic conditions in early nineteenth-century Pittsburgh; migration along the Ohio River valley; the differing construction of keelboats and flatboats; the education of the deaf; and what was in a pharmacist’s shop around 1825. By the time I was done with the story, the character with whom I’d started had evolved so unexpectedly that he never reached New Harmony at all. Waste, again, so much waste.

And yet— Not waste, because all that reading put me in a frame of mind emulating that of my characters. Ideally, fiction writers are trying to understand what our characters understand. No less than that; but also no more. Not what people later thought, after consideration and analysis, about the events through which our characters pass—but what our characters knew and saw and read and felt as they were living the moments they were living. Understanding analytically the world our characters inhabit isn’t much use; what helps is to understand what their world feels like, looks like: sensual details, images charged with emotion.

While researching for fiction, I always share Barrett’s goal: to understand what our characters understand. This is one of the reasons research can be so time-consuming and seemingly inefficient, especially if you’re writing far from your own subjective experience: it’s not enough to research mere setting details, although those are important too. Ideally, you want to get inside the heads of your character, then look back out at your story through that character’s worldview. A character’s worldview—like our own—is built out of personal experience, education or other learning, cultural context, job skills or special knowledges, and so much else. In other words, for a character to be believable, they have to know things. And the things they know are generally going to have to come from inside you—from your own experience and knowledge of other people’s minds—or from research.

Sometimes this blend is obvious, because it occurs at the edges of your personal experience. For instance, I wrote a scene last week where a character guts a deer, teaching another character the steps as he goes. I lived a version of that scene several times as a teenager, hunting with my dad, and I remember it well. But what happens next is a mystery: I grew up in a family where we took hunted deer to a local butcher for preparation, and so how a deer gets broke down into various cuts and so on was something I had to research before I could write it.

When Possible, Privilege Physical Research Materials

I’ve always done a lot of my research in physical books. Lately, I’m doing even more, prompted in part because large language models and AI are making search results much less reliable, and that AI-generated blob that opens every Google search result is often surprisingly inaccurate. (Plus: doing only online research often means finding the exact same first ten things that anyone else researching your subject will. You want to go farther, weirder, more unexpected places than the merely curious will!) But even before our ongoing AI apocalypse, I’d found there were tangible benefits of looking for facts in physical books, and for seeking out physical books in libraries and bookstores. In the end, I try to use Google not as a first resort but as my last: a web search too often takes me directly to the fact I’m looking for, which may or may not be the fact I need. Experience has taught me that much of the most useful material arrives via serendipity, as when looking up one term in a dictionary leads to an adjacent, unrelated word elsewhere on the page that turns out to be the one I actually need to solve a problem. Or while searching for one book in the library stacks, I discover a far more interesting volume hanging out a couple spines down from the one I’d planned to check out. If I hadn’t been walking the length of a bookshelf, I never would’ve seen it.

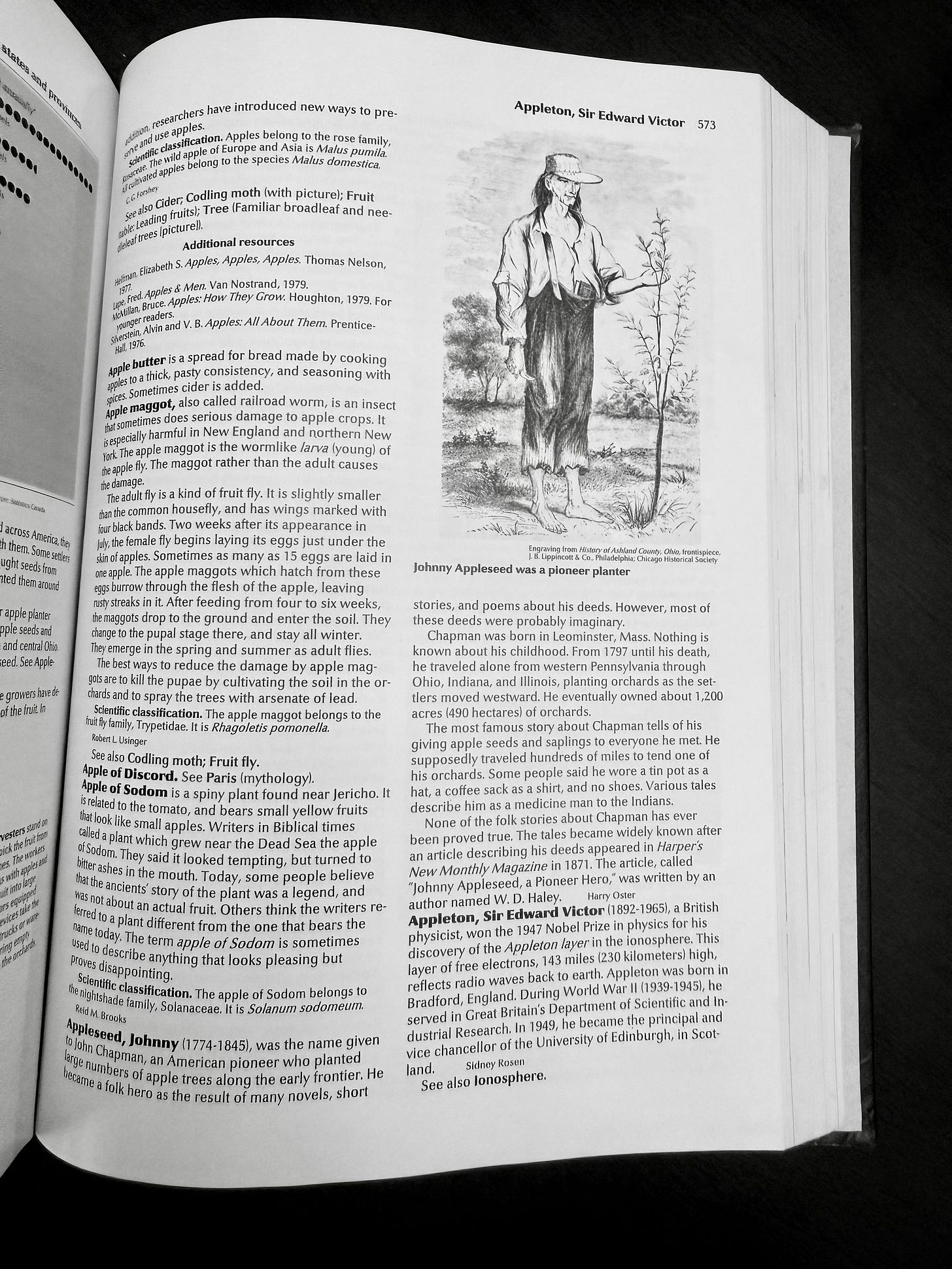

When you look for a fact or a definition in a physical book, your eyes see all the other facts and definitions printed on the page. Sometimes they’re immediately useful. Sometimes they’re just more fuel entering the machinery of your imagination and intellect. Either way, there’s a real pleasure to the adjacency effect that research in physical books or spaces offers, and following these various threads is one of the most enjoyable parts of research for me. Using the above photo as an example: if I look up my old pal “Johnny Appleseed” in my childhood 1989 World Book encyclopedias, I might also notice the entry for “apple maggot,” also called a “railroad worm,” an absolutely delightful piece of language. Who knows where that might be useful? And if even if its not, isn’t it likely that I’m still glad for the several minutes I spent in wonder thinking about it?

A side concern: which libraries are best? Do you need access to a university library or guarded archives to write good research-based fiction? Perhaps not. “I've long said that the best place to do research is in middle school libraries,” argues Allison Amend. “There's quality information there, but none of it too scholarly. You have to know a lot to write research-heavy fiction, but very little of it has to be in the manuscript for it to be convincing.”

Use Research to Generate Story and Character

But what should you do with all this material you’re reading? I wrote about this as best I could in Refuse to Be Done, so excuse me for quoting myself here, but here’s my best “rule” about research, especially in the first draft:

I never take notes separate from my main manuscript, especially once I’ve started writing. If I find a fact or a detail I want to include, I don’t write it down anywhere unless I can write it directly into the novel, either by finding an existing scene where it can live or by starting a new one centered on the fact or detail. That way, I don’t generate a separate document full of inert, non-novelistic prose, which feels so different from the kind of language I want my novel to contain. This practice has the side benefit of letting my research tell me what to write next: your research questions will guide you as powerfully as any whisperings of plot can, especially if you do your note-taking inside your novel, in the voice of the book.

This remains my preferred tactic, in large part because I want the research to always be generative, always be pushing the story forward or giving new life to my characters or their world. “The materials we’re using, whether autobiographical or historical, need to be dissolved entirely into the work,” writes Andrea Barrett, “freshly embodied in characters, images, and language bringing the scene alive for the characters and hence for us.” This is the truest goal of my generative approach to research: to shed an expert’s analysis in favor of a character’s embodied perception. What the character knows and feels and how they respond to the sensory details of their time and place is much of what fuels the fiction. Filter your research through a character by recording the research through their perspective, letting it inform their philosophies, their desires, and their sensory world.

Consume Media to Stock Up on Images

It takes so many details to fuel a novel, and at some point I always start running on empty: I’ve exhausted whatever I already know about my setting, repeating images over and over because there’s nothing else left. Here’s where the more visual mediums come in handy. If you’re lucky, there are documentaries about your topic or films whose stories unfold in your chosen place or time. (I watched Last of the Mohicans at one point for the express purpose of watching Daniel Day-Lewis run, a particular motion that I was sure was going to solve a problem in my novel—and did!) Video games can be helpful, if that’s your thing: while writing about the natural world, I’ve spent time wandering around virtual spaces like the well-rendered western environments of Red Dead Redemption 2, thinking about the ways a person navigates an unfamiliar and potentially perilous natural landscape. YouTube can be helpful for visiting far-flung places: where on Earth is left that someone else hasn’t already gone and made a video? I also buy coffee table books of related art or architecture or fashion, scouring the images for inspiration and the captions for relevant terminology. Museums are fantastic resources too, and not just for art: strolling through the artifacts of a historical exhibit can be incredibly tactile, allowing you to inhabit something you’ve only read about so far.

Of course, one of the best ways to refuel your image bank is leave the desk for the real world outside your door. So…

Gain Firsthand Experience Whenever You Can

If you have the opportunity and the means, it’s hard to overestimate the usefulness and the pleasure of visiting the places or settings you’re writing about. So many killer details come directly out of our personal experience of the world and can’t be gleaned in any other way. Because so much of what makes fiction pleasurable is the writer’s specific attention, the way their mind and heart moves through a space, I guarantee that even if you’ve read everything there is to read about a place, you’ll still see something new and unexpected if you go yourself.

One of the storylines in Appleseed takes place in a far future, re-glaciated North America, beginning atop the glacier, delving inside it, and eventually crossing a thousand-plus miles of its surface. I did a lot of research in books about polar exploration and about the science of glaciers, all of which helped. But in 2017, halfway through drafting the novel, I was in Iceland for work and decided to stay a couple extra days to hike in various parts of the country. One of those hikes was a guided half-day tour on the Falljökul Glacier in Skaftafell National Park, an unforgettable experience that also yielded up details I never would have imagined on my own. In the narrow crevasse pictured above, my companion put her ear to the side of the ice, then told me to do the same: we could hear water rushing inside the glacier, like an underground river flowing just below the surface. I didn’t understand the science of it but the sensation was pure magic. Later I wrote that magic into my novel, giving it to my character C, a bioengineered creature whose glacial passage would become much more fraught than mine: “In the lamplit crevasse, distance becomes ever more impossible to judge, sight reduced to a single beam of light, sound to his scrabbling hooves on the rocky ice, the huffing echoes of his breathing, the free water coursing inside the glacier, its gurgling trickle moving below the frozen surface.” It’s ultimately a minor note—the book doesn’t need it, in a load-bearing sense—but it certainly made my imagined scene more convincing to myself, which in turn gave me the confidence to keep going.

Saying “I hiked a glacier in Iceland for novel research” sounds pretty extravagant, and in many ways was: a lot of things aligned to make that possible, and certainly it wasn’t without cost. (And I know was lucky to have my employer buy the plane tickets.) But other in-person research has been essentially free, or at least cost little more than gas and time. In 2013, while revising my novel Scrapper—set amid the many abandoned buildings that then existed in contemporary Detroit—I drove down from where I was living in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula for research trips to the city. One day, I was joined by a photographer whose work documenting buildings as they were illegally scrapped I’d already used as a source, plus my architect brother, whose specialized knowledge was a huge help. I gained so much by having these two experts with me as I walked through buildings I’d been writing about, like the long-shuttered Packard Plant, and places I hadn’t yet visited, like St. Agnes Church, pictured above, where I found my book’s future epigraph printed on the dais. These trips changed the course of my novel in certain ways, but more importantly they changed its texture: there are so many details in Scrapper that came directly out of my experiences, and I believe my book would be deeply poorer without them.

If You Can’t Go, Search for Useful Analogues

Sometimes in-person research is prohibitively expensive. Or you can’t take the time off of work or away from familial responsibilities. Occasionally the place you want to go is too dangerous or too remote. In those cases, I might try to seek out useful analogues: where else might be “close enough” to get some flavor of the experience you might’ve had if you could’ve gone to the “right” place? This is also part of the toolkit for anyone writing science fiction or fantasy set in an invented place: For example, one of the novels I’m working on is set on an arid planet I can’t visit mostly because it’s, uh, not real. But I happen to live in the Sonoran Desert and to spend a lot of time out in its various environs—and so that invented planet forming in my mind has a lot of Sonoran Desert experience and research underpinning it. The places of our world are each unique but that doesn’t mean they don’t have rhymes in other locations, some of which might be closer to home. I’m doing my trekking this summer in Europe, because that’s the region I’m writing about—but couldn’t I walk just as far here in Arizona? Of course. And I’m sure I’d get at least some of the same experiences out of doing so: I imagine my legs won’t know or care whether it’s American or European miles that are exhausting them.

How Much Research is Too Much?

Where to stop with all this research? It’s a surprisingly personal question, situated at an intersection of interest and efficiency, ethics and authority. After all, How much research do you need to do? is a different question from How much do you want to do? Probably there’s no one right answer! Lauren Groff once called research “following the gleam in the dark,” saying, “It's about being sensitive enough to know which fact, as Virginia Woolf says, is ‘the creative fact; the fertile fact; the fact that suggests and engenders,’ as opposed to the fact that deadens and kills a delicate new project.” Somehow, we want to stay with those gleaming creative, fertile facts and experiences, while turning away from what bogs us down and makes the writing feel impossible. But where’s the line?

Years ago, I saw the novelist Will Chancellor read from his excellent debut novel, A Brave Man Seven Storeys Tall. Before he began, Chancellor explained that he’d tried to experience everything that he knew was going to happen, so as to make his novel more authentic: “Over the 10 years it took me to write Brave Man, I re-enacted as much of the plot as I could,” he wrote, in an essay that’s very close to what he said that night. Among other research experiences, he trekked across Iceland alone, a story he told to the audience the night I saw him. Here’s the version from his essay:

There are a lot of other examples of this book taking over my life, but the most striking, and nearly fatal, was my decision to traverse Iceland in 2009. I knew the story was always going to end there… and the research burden was too high to fake it. I tried twice and the results were horrid. So, after having written the climax of Brave Man four years prior in a New York coffee shop, I hiked across Iceland from the Snaefellsness Peninsula to Egilstaddir. Most of this was off-trail. I went weeks at a time without seeing anyone and had a few close scrapes when I deviated from the plan in favor of a shortcut. In the end, these two months of my life ended up being about two paragraphs of the book.

In the end, these two months of my life ended up being about two paragraphs of the book. It’s an extreme example of something that I think happens all the time to good novelists: you want to do your due diligence to be sure you’re getting something right, and that takes time and effort. (Chancellor’s research produced a great novel, so I’m only sharing his story to present an extreme, not to critique his results.) Maybe all that time and effort to produce such a small bit of prose that it hardly seems worth it. But ideally that time spent researching becomes earned authority that strengthens what ends up on the page—and sometimes that authority is also used to know what to leave out. Overexplaining can signal a lack of confidence, not unlike the need to include every bit of research a writer did, aiming to prove they did their homework to some imagined inspector.

One last example: While writing Appleseed, I realized that there was a part of the plot that revolved around gene banks, cloning, and genetic engineering, so I read tons of books and articles about CRISPR and 3D printing and other technologies. It took weeks, was genuinely interesting, and for a brief moment I felt like I really got it, despite my complete lack of a science background. I briefly, hubristically wondered, Could I get into a PhD program for genetic engineers? But after my research was complete, I wrote the only sentence that came directly out of all that reading, something that was better than this but not by much: “And then they edited the genes.”

I’m not even sure the sentence I wrote is in the final book. But I knew I needed to write it, and it was all the research I did beforehand and during revision that finally made me confident enough to be as straightforward as possible.

More soon, friends! Happy writing and researching!

Thanks so much for reading! If you’re not already subscribed, please consider doing so by clicking the button below.

Matt Bell’s novel Appleseed (a New York Times Notable book) was published by HarperCollins in July 2021. His craft book Refuse to Be Done, a guide to novel writing, rewriting, & revision, is out now from Soho Press. He’s also the author of the novels Scrapper and In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods, as well as the short story collection A Tree or a Person or a Wall, a non-fiction book about the classic video game Baldur’s Gate II, and several other titles. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Esquire, Tin House, Conjunctions, Fairy Tale Review, American Short Fiction, and many other publications. A native of Michigan, he teaches creative writing at Arizona State University.

![Dust and Light: On the Art of Fact in Fiction [Book] Dust and Light: On the Art of Fact in Fiction [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!FT1d!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0d2bf814-b280-4f29-a48d-502f53004485_1406x2250.jpeg)

“Either way, there’s a real pleasure to the adjacency effect that research in physical books or spaces offers, and following these various threads is one of the most enjoyable parts of research for me.” -- Agree, 100% this is also why I like getting the print newspaper. I read so many more articles outside my main wheelhouse than I’d ever click on.

Really fun post. For years my grandmother has sent me (& others) various documents & self published books about the area where her family is from. Being an oldest daughter I always kept them, but now that I’m writing a novel set in this region, they are chief among my research materials- full of first names, last names, kinds of trees. It’s bizarrely satisfying, even if shaping up the novel itself can be touch and go.

Have a great trip.