#58: Tips for a Successful Writing Retreat (and How to Make One at Home)

"A writer takes earnest measures to secure his solitude and then finds endless ways to squander it." —Don DeLillo

Hello friends! Happy New Year! Before we get started, a quick reminder that my “Revision, Rewriting, and Re-Visioning Writing Retreat” on the Greek island of Zakynthos still has slots available! If you’ve got a novel or memoir you’re working on and will be ready to revise or rewrite next summer, this might be a great fit for you. More info can be found at Uptrek’s website!

Tips for a Successful Writing Retreat (and How to Make One at Home)

Two things can be true at once: writers need time more than anything; writers never have enough time. Very few of us have truly abundant “free” time, our days divided between work, family and friends, community service and activism, church or other social groups, exercise and travel and dozens of other obligations, not to mention the bottomless well of content waiting to be scrolled or streamed. Even for those rare few who write as their primary profession, it’s easy to feel like not enough is getting done, or that other people are writing more and probably better.

Writers are obsessed with efficiency; efficiency is not a very good goal for writing. Still, most writers who’ve kept at it for any amount of time have found ways to squeeze writing productivity out of our days or weeks or years. For some people (this is me, most of the time), that means dedicating certain hours of certain days of the week to the work, steadily making progress alongside the rest of life. For others, it means the occasional all-night binge, bringing pent-up energy to the page and writing a whole story or a chapter from midnight to dawn. Many professors and teachers I know write only on weekends, or on breaks, or in the summer. Childcare and eldercare and other kinds of caretaking take incredible amounts of energy and offer no fixed schedule, making routine and solitude more difficult to establish, but many parents and caretakers still find a way to keep working on their projects, even if only at a glacial pace. (This was me over the past few years too.)

Which is all to say, writers are resilient and inventive but rarely get the chance to write in what feels like ideal circumstances. One solution to this quandary is the residency or retreat (two words I’ll use more or less interchangeably here, despite some differences), where a writer goes off to a secluded location for some period of time, putting aside as much of the rest of life as possible in order to write. It’s a rare pleasure, and probably unimaginable to some. I started writing when I was a college-dropout bartender who’d married young; as far as I remember, I never took a week-long vacation until the end of my twenties. The notion of getting two weeks or a month to do nothing but write was as remote a possibility as suddenly being offered a trip into outer space: cool if you could get it, but nothing I expected to come my way.

In my 25 years of serious writing, I’ve only had four proper writing residencies, all in the last ten years or so. I’ve twice been asked to be a visiting writer at the Vermont Studio Center, where I had some duties (a reading, a craft talk, meetings with the writers working there at the time) but otherwise had a week alone in a writing studio; a month at the Writer’s Retreat-Puycelsi in France (during the tail end of COVID lockdown, which presented its own challenges); and one just last month, at the San Ysidro Ranch Writer’s Residency in South Texas. VSC is a communal space with lots of other writers and visual artists around; both Puycelsi and San Ysidro are solo affairs, with only one writer on-site at a time.

What follows below is what I’ve learned from these experiences about how to make them work for me, as well as what lessons I’ve extrapolated for home or smaller-scale “staycation” retreats, which I also occasionally create for myself. Obviously, everyone works differently and has different needs, so keep what’s useful and throw away the rest. But for me, these tactics have been successful: I wrote 25,000 words of the last act of Appleseed in one of those weeks at VSC, for instance, and I just wrote the back half of a novel’s second draft in two weeks in Texas. (Obviously, the next step in both cases was revision: at that pace, these were never going to be clean pages.) The ability to write that fast has everything to do with how I prep and how I conduct my days there, so here’s hoping some of what I’ve learned might help you too.

Before going on, it’s worth acknowledging up front that the residency/retreat system has its own layers of gatekeepers, expense, and accessibility issues. Even if a weeks-long residency is offered, it can feel impossible to accept without burning all your vacation time, or without putting undue burdens on partners to care for children and pets and so much else. These days, I’m a professor who doesn’t teach in the summer and who lives alone: I realize I have more say over how I spend my free time than most people. But what isn’t possible at one life stage might become so later, and there are ways to make your own mini-retreats at home or nearby. As I proceed below, I’ll try to also adapt everything I have to say about residencies to smaller periods of devoted work, even those occurring inside the home. I’ve finished many a draft over a long weekend while my former partner was away on a solo trip: it’s amazing what even forty-eight hours of alone time focused well can generate, if you’re primed to make of the time.

Last bit of this long preamble: I won’t go into how to apply for residencies and retreats, because that information is covered so well other places. If you’d like more on that end of things, check out this essay by Rebecca Makkai, which gets into not only the hows and wheres but also what happens when you apply and how scholarships and other kinds of funding tend to work.

Go at the Right Time for Your Process

There’s probably no wrong time for a residency but there might be a right one. For me, the best time seems to be later in the process, when the project is mature enough that I have a critical mass of pages and a good sense of where the book is going. I’ve only shown up once at the start of a project: for my first VSC week, I had a handful of pages and some notes for a new novel; I wrote 30,000 words in my cabin and then never worked on it again. It still may have been a win—my novel wasn’t going to work, and I figured that out in a week instead of six months of a year—but it didn’t feel like one.

For me, the challenge of unlimited time at the beginning is mostly because it’s an achievement if I can write 500 words in a sitting when I’m starting out. It’s all the usual problems: I’m not fully committed yet; I don’t know the protagonist well enough to guess what they’ll do in any given scene; the voice isn’t calibrated right, making my prose slow and unsure. I write a couple pages and then I think about them overnight and then maybe I write a couple more the next day. If I try to write faster than that, things get sloppy fast.

But later in a project—and especially in a second draft, which for me means writing again from scratch but with an outline at my side and a much fuller understanding of the book—I can work very long days if given the opportunity. During my most recent residency, I wrote between 3000 and 5000 words a day, with one 6000-word day outlier. There’s no way I could’ve done that earlier in the process. There’s probably no way I could’ve done it even at the beginning of this second draft. But by the time I arrived at San Ysidro, the wave of the story was coming in and all I had to do was ride it. That’s where residency really works for me.

Home adaptation: Again, this is all about picking your moments. If you’re a writer like me who only really benefits from big stretches of time to work late in a project, there’s no point in burning currency with your partner or family or job too early. Learn when the best phases for dedicated writing are for you, and wait until you’re ready to set up your retreat or even just to try to make longer hours work in your life. The creative life is cyclical—mine is, at least—and it’s good to know what season of the project you’re in and what it requires of you.

Aim at the Residency Before You Arrive

In 2018, I was working on the second draft of Appleseed when I was offered a second visiting writer gig at VSC for March 2019. Immediately, I used that to set a goal: knowing how much I might be able to write there, based on my earlier “failure,” I decided I’d do everything I could to be ready to finish by the time I arrived in Vermont. I’m good with deadlines, good with goals: as soon as one appears, I orient my life around it. (I’m also good at forgiving myself when I miss them.) I can remember a conversation with a colleague in November where I said I was doing everything I could to hit the holiday break running, in hopes of getting enough done to meet my March target. I made good progress throughout early 2019, and by the time February I rolled around I was into the third act of the book.

I had an outline but by then the actual plot had diverged greatly. So two weeks before I left for VSC, I paused to make a bulleted list of the scenes I thought I had left to write, one for each of that novel’s storylines. This mini-outline wouldn’t turn out to be exactly right either—I’d be suspicious of any outline that was—but it served an important function. When you’re working long days—and in a residency, I can write eight or ten or twelve hours a day—the most obvious places to quit are when you finish a scene or a chapter. Having a list of what’s next is crucial for keeping up momentum. Same thing if a scene goes sideways or falls apart: sometimes I stay until I get it, sometimes I move on to the next one in the list, which often reveals how to fix the previous one. (Equally often, the previous scene turns out to be unnecessary.)

The mini-outline also provides a sense of progress. Write a scene, cross the scene off the list. See the list slowly become more crossed out than not. It’s deeply satisfying. It might be enough encouragement to keep you writing late into the evening.

Home adaptation: Everything above should work the same whether you’ve carved out forty-eight hours or the next four Saturdays or whatever your time duration is. Knowing what you’re supposed to do next saves so much time. Putting the list where you can see it in the lead-up to your mini-residency will keep your brain working on the problems and possibilities the list suggests.

Establish Your Writing Space (And Only Use It for Writing)

Most every residency or retreat space will have an obvious work space, usually a very nice desk and a chair that works nights as an instrument of torture. (The one thing I regret not throwing in my car before leaving for Texas is my desk chair, an insane thing to bring across the country, an insanity I considered and wish I’d indulged.) Maybe there’s a lamp, maybe a printer, probably a row of books written by former residents or research materials abandoned by the same. The rest is up to you.

My tech setup for my last two residencies (France and Texas) has been reasonably simple: my MacBook, a folding stand that elevates it to eye level, my full-size keyboard, and my ergonomic trackball mouse. It’s basically exactly the same as at home, except there I plug my laptop into a widescreen monitor. (I thought about bringing my monitor to Texas too.) It’s not much but it’s enough: I can’t imagine working as much as I have the past two weeks staring down at a laptop, or using their cramped keyboards and trackpad. Even flying internationally, these extras take up almost nothing in a suitcase and are worth every ounce.

Beyond that, I bring along a pile of research books, some of which I’ve previously studied, some of which I haven’t opened but think I might need. I always bring a stack of research; I rarely touch the research materials. But having the books nearby is a kind of externalized memory: I don’t have to reread the books to remember some of what I read in them. I think I’d have a harder time without them.

The final thing I added to the desk in Texas was a picture of me and my partner, taken during a favorite adventure together. You’re going to spend a lot of time alone at this desk. It’s not a bad idea to occasionally look up and see your loved ones looking back at you.

Once I’m set up, my rule is that as much as possible, I don’t do anything but write at the desk. I try not to browse the internet or do social media; I don’t stream movies or shows at night there, if there’s another space available. I want it to be almost trance-like when I sit down, my body and mind primed to act as soon as I arrive: if I’m in this chair, I’m writing. If I’m not, I’m not. It’s amazing how much that helps me keep going.

Home adaptation: Not every living situation offers a dedicated space for writing but in my ideal world, there’s a set-aside place where I only write, for all the reasons above. That said, I think there are lots of ways to create the trance-like feeling of the dedicated space no matter where you are. I was writing my second novel while I was on book tour for my first, and in those days I was crazy enough that I still wrote most days even when traveling for work. (I’m a little gentler on myself now.) That year, I found I could work anywhere, because all I really needed to create the trance state was music, specifically music that I only listened to while writing. For years, this was the surest way for me to induce a work state: I’d put on my headphones and fire up a custom playlist as a kind of “audio office.”

Time of day can work as well as place: I write at the exact same time most days, and so reduce the decision-making involved with sitting down to write. It’s just the time to do it and so I do it. When I was a restaurant manager working 60 hours a week, I would take my work schedule for the month and schedule five two-hour blocks a week on the same calendar. I treated it exactly the same way: if the calendar said it was time to write from 11-1 that day, I sat down and did it like it was my job. It sounds robotic or uninspired, perhaps, but for me, surrendering to the schedule makes inspiration possible.

Build a Routine

One of the paradoxes of our busy lives is that sometimes unstructured time is very hard to spend well; the routine of the semester keeps me on track in ways that summer break does not. In a residency, one goal of the first days to figure out the how and when of my work day in the new space. This time, in Texas, I decided to go dream to desk as often as possible, getting up and immediately writing for an hour or so before I even made coffee. After coffee, I’d work another hour and then I’d have a simple breakfast before getting back to it until 11am or so, when I’d go for a five-mile run. After my run was a shower and lunch and then back to writing until an hour before sunset, when I’d crack a beer and take it on a walk for a couple miles. Then dinner and more writing for as long as I could, usually a couple hours more. The next day, I’d get up and do it all again. It wasn’t a thrilling life. The sameness of the days let me seek my thrills at the desk instead.

Home adaptation: This might be the one that’s the hardest to emulate in your real life. The demands on us can be wildly different from day to day or week to week, and even the best laid plans tend to be interrupted by emergencies. (I literally stepped away in the middle of drafting this paragraph to handle an unexpected problem.) When my routine fails, the place where I reclaim my writing time at home is usually from my entertainment budget: I loved peak TV as much as anyone else, but I have never regretting reading or writing instead of watching TV. I have to remind myself of this almost every single day.

Spend as Little Time as Possible Deciding What to Eat

As strange as it might sound, this might be the actual most important piece of advice here. I love to cook. I have dozens of cookbooks in my kitchen, spend a gross amount of time on NYT Cooking, and consider a couple hours spent putting together a good meal one of the best uses of an evening. For a couple of years, I was regularly cooking 100 new recipes a year. But it’s all so time-consuming, and even more so if you’ve got a picky family or other people you have to accommodate by cooking three or four meals at once. (And all of that’s before you do the dishes.)

As mentioned above, my first two residencies were at the Vermont Studio Center, where they serve three meals a day in their cafeteria. If I remember right, breakfast was 6-7am, lunch was 12-1pm, and dinner was 6-7pm. The food was always pretty good! But the real benefit was that for seven days I didn’t think for one second about what groceries I needed, about what I was going to cook, about how long it would take. I just walked from my studio to the cafeteria at the appointed time, ate, and walked back. It freed so much brainspace to have this handled, and I’ve never forgotten the lesson.

In my solo residencies, I’ve done all of my own cooking but I’ve still worked to lessen the burden. Maybe at home I would make something more ornate any night I’m home, but in residency simple was better. In France, the bread and cheese and wine was so good that many a meal was just those three ingredients. In Texas, I had a protein shake or bar for breakfast every day, a sandwich or a can of soup for most lunches, and for dinner I made a one-serving deli meal from Texas grocery chain H-E-B, which offers fresh meals for one that don’t require anything more than throwing them in the oven an hour before you want to eat. A deli plate of salmon and roasted veggies felt pretty indulgent, tasted good, and didn’t ask much of me! It’s not the way I’d do it at home but it was perfect for residency.

Home adaptation: Every bit of brain you free from daily life maintenance suddenly becomes available to you for writing. Feeding yourself and your people is an important part of life, and one of its great pleasures. But it’s also one of the places you might be able to occasionally simplify, especially for a short period of time. I once meal-prepped lunches and dinners in advance for me and my partner for the six days I needed to finish a project so I wouldn’t have to think about food for a week. I still had dinner on the table every night when she got home but it didn’t cost me much new effort.

Read a Craft Book for Writerly Company

One thing I’ve found super helpful is to bring along a single craft book, usually something I haven’t read yet. Every time I sit down at the desk, I pick it up and read until something inspires me or surprises me or makes me excited to write. It never takes long, if the craft book is any good. I do the same thing whenever I get stuck or feel restless. Instead of leaving the desk, I read the craft book until I want to write again. It’s so helpful. In Texas, it was Elizabeth McCracken’s A Long Game keeping me company. It’s fantastic, and I can’t recommend it enough.

Home adaptation: This one’s easy! It works just as well wherever you’re writing, and it’s something I need to remember to do more at home too.

I hope all of this is helpful, if and when you get the chance do to an official residency or to make one for yourself. If you’ve done either kind of residency before and have your own tips for making the most of th experience, feel free to put them in the comments!

Good luck with your writing this month! More soon, friends.

Thanks so much for reading! If you’re not already subscribed, please consider doing so by clicking the button below.

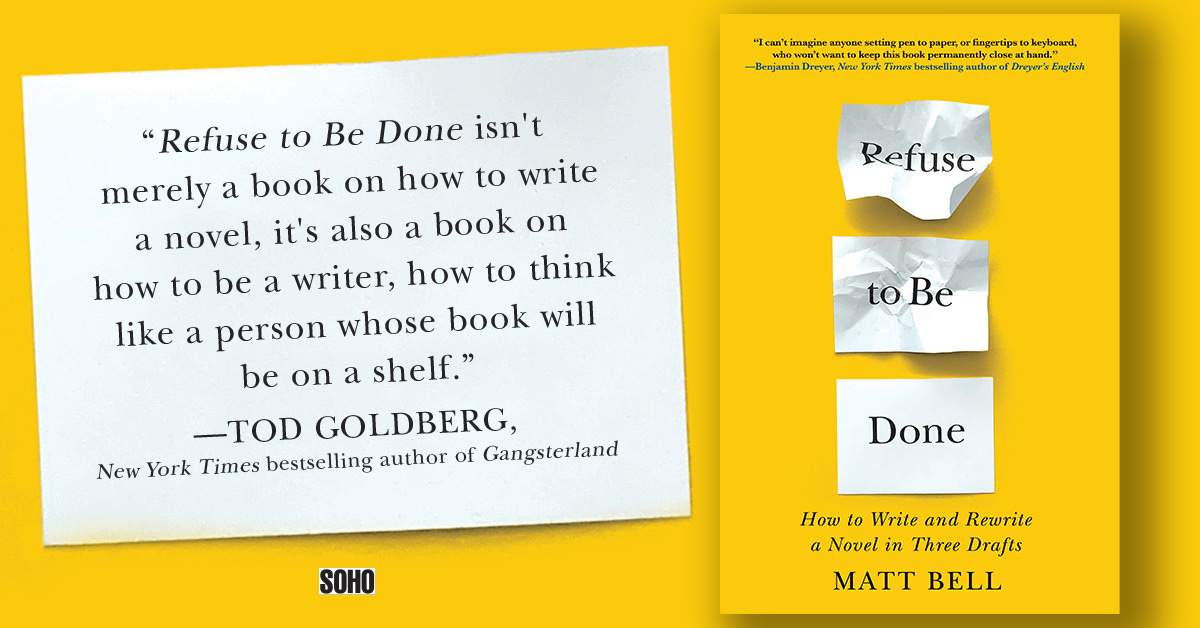

Matt Bell’s novel Appleseed (a New York Times Notable book) was published by HarperCollins in July 2021. His craft book Refuse to Be Done, a guide to novel writing, rewriting, & revision, is out now from Soho Press. He’s also the author of the novels Scrapper and In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods, as well as the short story collection A Tree or a Person or a Wall, a non-fiction book about the classic video game Baldur’s Gate II, and several other titles. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Esquire, Tin House, Conjunctions, Fairy Tale Review, American Short Fiction, and many other publications. A native of Michigan, he teaches creative writing at Arizona State University.

love the confirmation on the necessary but deviant outline and the specifics regarding your discipline. i often teach when i think i shouldn't for fear of not using my time wisely and feeling sore about the lost lucre. obviously not an uncommon. love Refuse to be Done as well. and the research books as a talisman of sorts. comforting.

So helpful and encouraging- thank you for sharing 🤗