APPLESEED launch day! / Exercise #19: Retelling Myths, Folklore, and Fairy Tales

“A gripping meditation on manifest destiny and humanity's relationship to this endangered planet, making for a breathtaking novel of ideas unlike anything you've ever read.” —Esquire

Hi friends,

Today’s the day: My novel Appleseed is now available wherever you buy your books! Here’s the quick pitch: Appleseed is an epic speculative environmental novel, told across three storylines and a thousand years. It begins in the late eighteenth century with a mythological retelling of Johnny Appleseed, continues in the late twenty-first century with the story of a resistance movement activated by a climate change-caused political collapse and a plot to geoengineer the atmosphere, and then leaps seven hundred years more into the future to follow a bioengineered creature living alone atop a glacier that spans half of North America. It's a story about manifest destiny and the climate crisis, about how we got here and about how people in the future might try to solve the environmental and culture problems we've made; it's a mythological epic, a technological thriller, a big adventure story set in the past and present and future.

I woke up this morning to the surprise of a rave launch day review in the New York Times Book Review from Laird Hunt, who concludes, “Bell has achieved something special here. Appleseed, a highly welcome addition to the growing canon of first-rate contemporary climate fiction, feels timely, prescient, and true.” The novel’s received other positive reviews in the Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Review of Books, The Brooklyn Rail, Alta, and elsewhere, and was named one of the best books of the summer by Esquire, USA Today, Book Riot, The Philadelphia Inquirer, and other publications. (Esquire also published an excerpt, which you can read here.) It’s also been selected as an August Indie Next List pick and as one of Amazon’s Top Books of July.

Thanks so much to everyone who’s already ordered a copy or is planning on picking one up at their favorite local bookstore! If you desire a signed hardcover, Changing Hands in Phoenix/Tempe will ship one to you wherever you are: I’ll be heading there tomorrow to personalize any copies you order today.

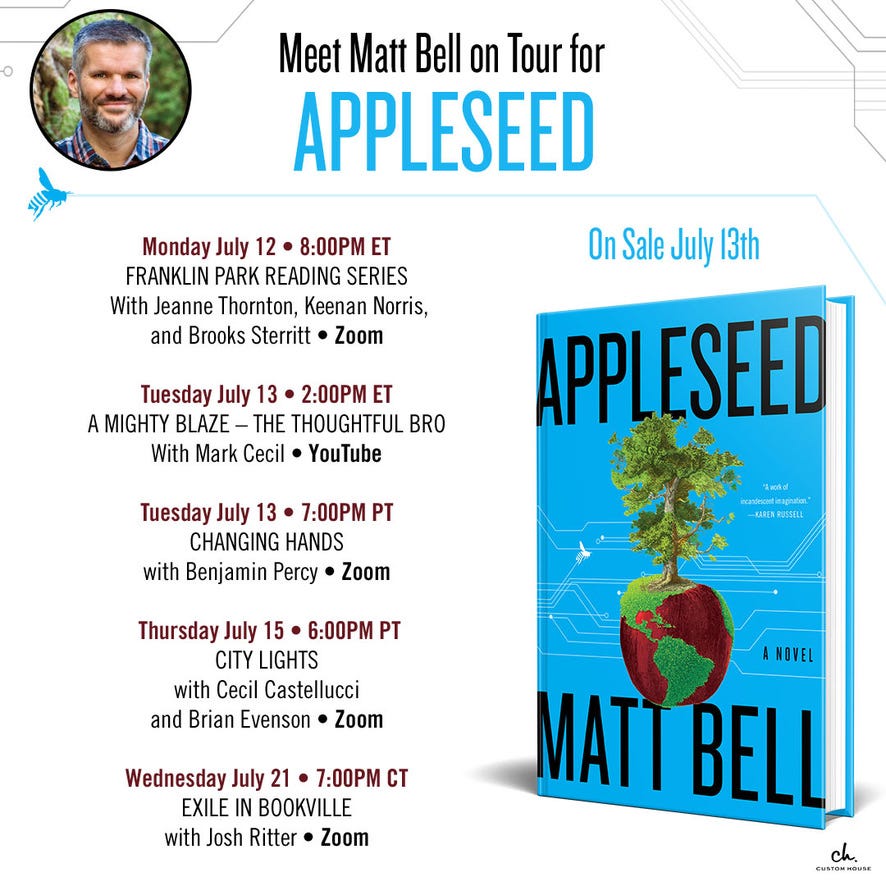

If you’d like to attend one of my virtual book launch events this week or next, I’d love to see you! Here’s the tour schedule, with links below:

July 12: Franklin Park Reading Series, Brooklyn, NY (with Jeanne Thornton, Keenan Norris, and Brooks Sterritt)

July 13: “The Thoughtful Bro”/A Mighty Blaze (with Mark Cecil)

July 13: Changing Hands, Phoenix, AZ (with Benjamin Percy)

July 14: Wednesday Night Sessions at KickstART Farmington, Farmington, MI (with Mitchell Nobis)

July 15: City Lights, San Francisco, CA (with Cecil Castellucci and Brian Evenson)

July 21: Exile in Bookville, Chicago, IL (with Josh Ritter)

Okay, that’s enough of that! As promised, I’ve tucked a bonus exercise below as a thank you for putting up with my launch day self-promotion above. Enjoy, be safe, be kind, and happy reading and writing!

Yours,

Matt

Exercise #19: Retelling Myths, Folklore, and Fairy Tales

As long as I’ve been writing, I’ve been attracted to writing new retellings of myths and fairy tales and folklore, in part because I’ve loved reading those kinds of stories my entire life. (The most natural stories to write are usually those most like the stories you love to read.) As I said above, my novel Appleseed started out as an attempt to retell the American folk tale of Johnny Appleseed through a mythological lens, recasting the historical John Chapman as a half-human, half-animal faun from Greek myth—but as I wrote, other myths and stories also became central to the novel’s plot. Because one of the most memorable fauns or satyrs in myth is the one who appears at Orpheus and Eurydice’s wedding (in some tellings), I started folding in elements of that tale as well; soon I was adding a version of the Furies and the Fates, adapting what I remembered of their myths to my own needs, importing these characters from Ancient Greece to 18th century America. And once I started writing about apples and apple trees, it seemed impossible to avoid thinking about the Garden of Eden, especially since the Genesis-related issues of stewardship and dominion over the Earth were so central to the story I was trying to tell.

That’s a lot of different myth-systems to incorporate and make work with each other! But teasing out what was interesting to me about each of them and figuring out how to integrate those pieces into one big story was a large part of the fun of writing Appleseed, as it always is when I start working with these kind of tales.

Many of my favorite contemporary writers frequently traffic in new fairy tales and myths too, either through retellings or through the invention of tales all their own, writers like Kate Bernheimer, Amber Sparks, Karen Russell, Rikki Ducornet, Brian Evenson, Helen Oyeyemi, Lily Hoang, Aimee Bender, Kelly Link, among many others. (If you’re a similar writer and haven’t found all your people yet, Bernheimer’s Fairy Tale Review remains the best place I know to go looking.) I learned so much of what I know about retellings from these writers, and I continue to take pleasure from the unending invention and reinvention I find in their latest works.

One of the things I personally like best about myths and fairy tales and folklore is how inexhaustible they seem. Many of my favorite tales have been told and retold across cultures and across geographies, across time and place and in different technological eras, usually without diminishing or harming the building blocks of the core story: at the center of each of these durable tales, there is some set of characters, objects, or places that can be endlessly permutated to produce new versions that become part of the long history of the tale while also being their own new thing.

Here’s an example. My favorite fairy tale is probably Little Red Riding Hood, which in its earliest oral forms is probably at least a thousand years old, and probably older. I probably first encountered it as a kid in a version of the Grimm brothers from the early 19th century, although likely in a retelling in an illustrated children’s book. I’ve since read dozens of versions of this tale—and written my own.

Years ago, I wrote a version of Little Red Riding Hood titled “Wolf Parts” (PDF here, if you’d like), which began with a version of the exercise below, a then-experimental process that soon became a tool I reach for whenever I’m working with a fairy tale or myth. It’s not always the way I start out—I usually begin from a single remembered image or action, rather than a comprehensive study of the tale—but it’s a good practice for generative research and revision.

Here’s what I do. At some point in my process, I reread the tale I’m working with—sometimes many versions of it—to try to identify the central building blocks of the story, then I find new ways of fitting them together. For “Wolf Parts,” I reread a half-dozen classic versions of Red Riding Hood—the Grimm version, the Perault version, the similar East Asian tale (and possible precursor) “Grandaunt Tiger,” and others—and tried to find the story’s basic building blocks that appear is some (if not all) versions of it. In Little Red Riding Hood, those building blocks include a young girl, a mother, a grandmother, a basket of food, the wolf, a grandmother, a woodsman, a woodsman’s axe, the woods (and a path through the woods), a shared meal, the grandmother’s clothes, needles and string and thread, the consumption of people and flesh, the inside of the wolf’s stomach, and probably a handful of other things I’m forgetting now.

Once I have this list, I might play around with these elements, seeing what interests me the most or feels most generative, sometimes trying out one combination after another, just because it’s fun. In “Wolf Parts,” that remained the mode of the whole story: it’s made up of 40 micro-permutations of the elements I identified, some of the tellings fairly straightforward, some a bit stranger. But usually it’s a little less exhaustive of a process: I simply pick what feel like the most interesting parts of the original story and then get writing, often using the tactics below.

To begin today’s exercise, choose a favorite version of a fairy tale, myth, or folk tale, then read through it making a list of the prominent characters, places, objects, and actions you find. Once you have this list—let’s assume you’ll have at least ten items—pick one of the following prompts:

1) Take one of the more surprising elements you found (so not the title character, and not the most famous action) and place it at the center of a new tale. What new story can you find by telling it from this new perspective or place or by making a previously minor character the POV character? For instance, in one traditional version of Little Red Riding Hood, there’s a cat who appears in only one sentence to call Red a “slut” for eating the flesh and blood of her grandmother: what’s that cat’s story? What happens when it takes on a starring role?

2) Reverse the usual role of the characters in the story. This is perhaps one of the most obvious transformations you can make, but I’ve found it to be a fascinating one to play around with: what happens in Little Red Riding Hood when you make the girl the aggressor, instead of the wolf? What if it’s the wolf that saves the girl from the grandmother or the woodsman, instead of the other way around?

3) Change who possesses or uses what objects in the story. Taking the woodsman’s axe and putting it in Red’s hands might equalize the power differential between her and the wolf, when they meet upon the woody path… or it might only make the wolf angry.

4) Multiply the number of occurrences of one element in the story. What happens to “Little Red Riding Hood” when you make it a tale about a family of sisters, instead of one girl? What happens when you add in a series of wolves, appearing in sequence or at different times of Red’s life? What if the woods were crawling with woodsmen, each one armed and looking to engage in random acts of unasked-for heroism?

5) Make a second list from another tale or myth, then start swapping parts: what happens to the objects of one tale when they’re made to appear in another? One of my other favorite fairy tales is Rumpelstiltskin, who in many tellings tears himself in half in frustration once his real name is revealed and his plot foiled: what if this quality was given to the wolf in Little Red Riding Hood, who might then be made to free Red from his stomach in a fit of violent anger prompted by being defeated in wordplay?

Good luck! See you in August!

Thanks so much for reading! If you’re not already subscribed, please consider doing so by clicking the button below. This post is also publicly accessible, so feel free to share!

Matt Bell’s novel Appleseed was published Custom House in July 2021. His craft book Refuse to Be Done, a guide to novel writing, rewriting, & revision, will follow in early 2022 from Soho Press. He’s also the author of the novels Scrapper and In the House upon the Dirt between the Lake and the Woods, as well as the short story collection A Tree or a Person or a Wall, a non-fiction book about the classic video game Baldur’s Gate II, and several other titles. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Tin House, Conjunctions, Fairy Tale Review, American Short Fiction, and many other publications. A native of Michigan, he teaches creative writing at Arizona State University.