Exercise #15: Suspense-Generating Summaries

Nnedi Okorafor, Matthew Gavin Frank, Annalee Newitz, Megan Campbell, Ander Monson, Anthony Doerr, Jim Shepard, China Miéville

Hi friends,

I’m going to start this month by telling a quick story about a decision I made when I started this newsletter, on my way to making an ask of you: if you’d like to skip all that and get right to the exercise, feel free. Scroll down! Enjoy!

If you’re still with me, thank you!

When I started this newsletter last March, I knew from the start that I would always offer it only for free. I didn’t even turn on the option to let you voluntarily pay for it, if you wanted, because I wanted the newsletter to be something that passed between us without money changing hands, a gift and a conversation instead of a job for me and a transaction for you. I’m thankful for the terms that decision set: I write exercises, you try them out in your fiction, we chat about them on Twitter, sometimes you tell me you got something published that started here. It’s exactly what I hoped for, and enough!

But of course, I am also occasionally publishing books, and those I would also love to get into as many hands as possible, when the time comes. Including yours!

My new novel Appleseed is out on July 13, which means we’re about ten weeks away from its pub date. As you may know, preorders are increasingly key to a novel success, in part because they help get it into bookstores and libraries in larger numbers. So here’s my ask: if you’ve enjoyed this newsletter and found it to have value in your life as a reader and a writer, will you consider preordering a copy of my new novel?

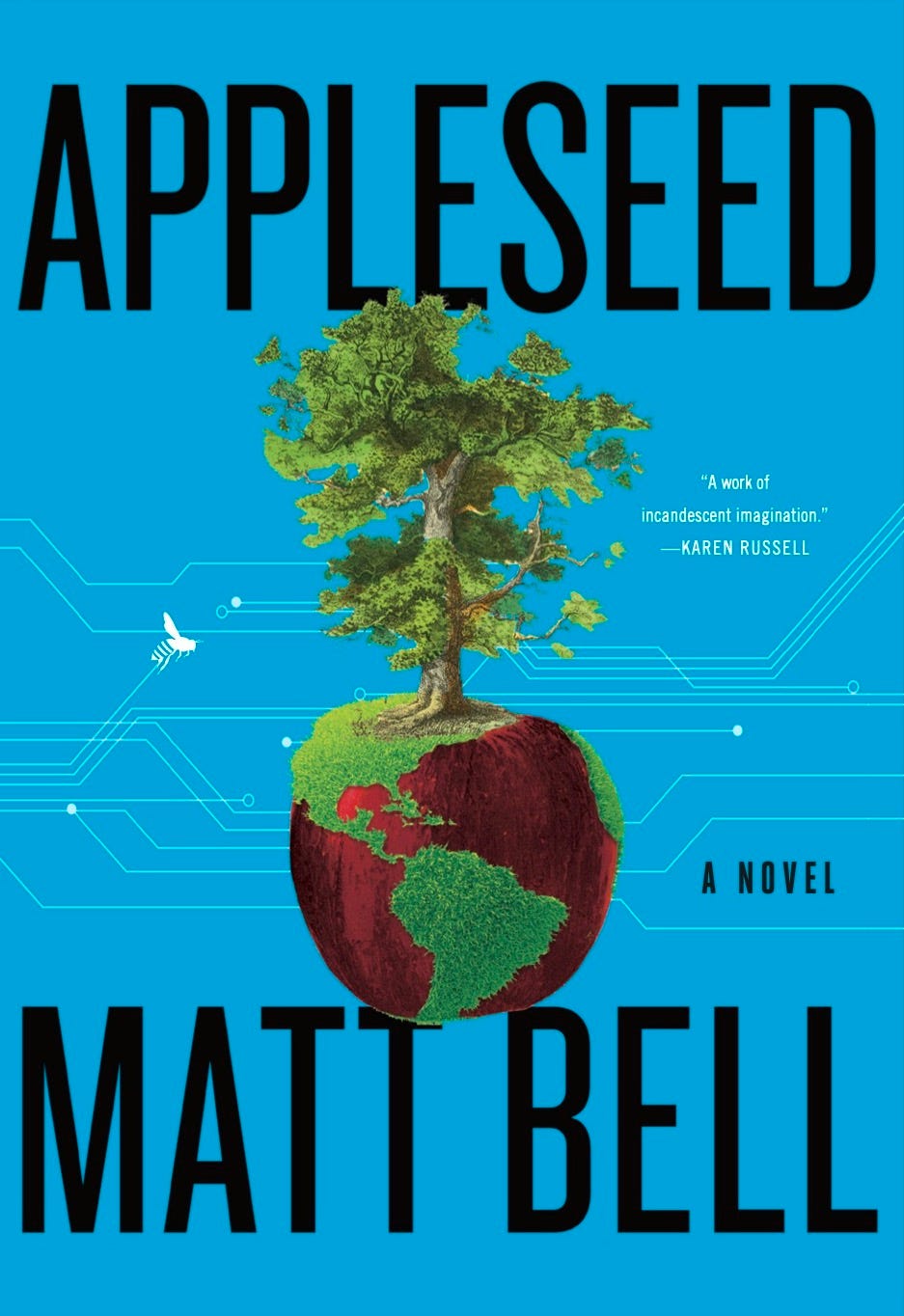

The quick pitch: Appleseed is an epic speculative environmental novel, part mythological retelling, part eco-thriller, part sci-fi adventure tale, beginning in the late 18th century and ending a thousand years later: it’s about climate change, manifest destiny, settler colonialism, geoengineering, 3D-bioprinting, extinction and immortality and so much more. (There are also mythological creatures and shapeshifting witches and nanoswarms of bees and…) Karen Russell called it “a work of incandescent imagination”; Kelly Link said it is “as urgent as it is audacious”; Aimee Bender said “it’s a beautiful tribute to what fiction can do.”

Here’s a look at the final front cover, the face of what’s going to be a big blue book:

That’s it: commerce concluded. Thanks for putting up with it, and thanks to everyone who preorders Appleseed today, from their favorite indie bookseller or wherever they prefer to buy their books. I’m so grateful to you all.

Onward! As always, if you write something you like using this month’s exercise, feel free to tell me so. You’re also welcome to pass this prompt on to others, if you’d like, either by forwarding the email or sharing the link on social media. If you do, know that I appreciate it.

Be safe this month, be kind to each other, and good luck with the exercise!

Happy writing,

Matt

www.mattbell.com

What I’m Reading:

Remote Control by Nnedi Okorafor. I love Okorafor’s fiction, and this short novella is another fantastic addition to her body of work. Like the Binti books, its pleasures begin with how great of a character Sankofa is, but I’ll be thinking of the plot structure here for a long time too: it moves in unexpected ways, perhaps more like a folktale than typical science fiction, and I know I’m not done thinking about how it works.

Flight of the Diamond Smugglers by Matthew Gavin Frank. I’ve had the pleasure of knowing Matt Frank for a long time, as a friend and colleague from my time in Marquette in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and as a fan of his nonfiction writing. His latest is a fantastic travelogue set in South Africa, a personal story about moving on from loss, and a great look at the surprisingly interesting lives of carrier pigeons—which sometimes include smuggling diamonds.

Four Lost Cities by Annalee Newitz. If you’re stuck at home and looking for a fresh injection of wonder, I highly recommend Four Lost Cities, where Newitz visits and researches the ruins of the ancient cities of Çatalhöyük in Central Turkey, Pompeii in Italy, Angkor in Cambodia, and the Cahokia in what’s now Illinois. It’s such a smart, fun book, and Newitz does a great job connecting these ancient cities to our present-day urban lives.

March Plaidness. For years now, Megan Campbell and Ander Monson have put on an annual tournament pitting 64 essayists representing 64 songs against each other in friendly competition: they’ve done March Sadness, March Fadness, March Shredness, and March Vladness in years past, and this year they finally arrived at March Plaidness, the grunge and 90s alternative tournament. It always produces incredible nonfiction work, and this year’s essays might be the best yet.

Exercise #15: Suspense-Generating Summaries

I’m getting increasingly deep into the second draft of a novel, which has me thinking constantly about suspense and proportion: how can I arrange the material of the plot into the most tense and compelling version of itself? How long should chapters or acts or parts or whatever divisions I’m using be? Can I solve these questions at this stage, or will I have to wait to figure it out?

Answers: It depends! I don’t know! Probably I have to wait!

So maybe I can’t already know exactly how everything should go—there is so much trial and error in my process, even in later drafts—but I can keep thinking about how suspense is created, and how it can be used to pull the reader through a novel or a story. There’s so much to say on suspense, which is surely a bigger topic than this exercise can contain, but for our purposes today I want to put two bits of craft on the table, both from Anthony Doerr.

One of the best craft essays I know of on suspense is Anthony Doerr’s “The Sword of Damocles: On Suspense, Shower Murders, and Shooting People on the Beach,” from the The Writer's Notebook II, where Doerr writes:

In almost every suspenseful moment in the history of drama, a hero (and therefore also a reader) finds herself caught between two points and dangles there a while, on the threshold between two worlds, suspended, before crossing over to one of two poles. Suspense happens in the pause, the drawing out, the tense, vibrating position as our hero hovers above the abyss, before the large-scale dramatic questions get answered—Will she fall? Will she cross to safety?—a place where the hero (and therefore the reader) feels both the intoxication of gravity and the terror of it, before these emotions are resolved. These moments are at the heart of storytelling.

In his essay, Doerr makes much of how suspense and suspended share the same root, and of how excitement in storytelling comes not from speeding up but from slowing down, from creating pauses or instances of dilated time in the most exciting parts of the story: “interruptions,” he writes, “can build intensity, rather than sap it.”

He also talks about the term “rate of revelation,” which I first heard of from interviews with Jim Shepard, and which Doerr summarizes as follows: “How quickly do you want to unspool your secrets? How quickly do you want to answer the dramatic questions you’ve posed? How quickly do you want to let your reader know everything that you (the storyteller) know?”

Okay, so we’ve got two pieces here: we’ve got suspense, which can be built by interrupting actions with other kinds of text, like digressions, descriptions, and interiority; and we’ve got the rate of revelation, the pace at which readers learn about characters, plot, and the world. What can we do with these ideas, in our stories?

Plenty! But I want to focus on one of my favorite moves today, what I think of as “suspense-generating summaries,” which is what happens when you interrupt a tense action-filled scene or story to summarize the plot so far, primarily to delay the resolution of the action currently in progress.

For our first example, let’s turn to Anthony Doerr’s own story “The Caretaker,” from his debut The Shell Collector, which follows Joseph, a Liberian cement company clerk, embezzler and eventual fence for stolen goods, whose story properly begins when his mother vanishes during a trip to the market near their home outside Monrovia. Civil war breaks out, and Joseph leaves his home in search of his missing mother, a misadventure which eventually leads to him murdering a stranger, fleeing the war as a refugee until he arrives in Oregon, where he’s hired as a caretaker for the home of a man named Twyman, a job He neglects until he’s fired. Joseph next moves into the nearby woods, where he plants a garden (with stolen seeds and tools) and lives furtively for several months, until one night he falls asleep on the beach, exhausted, waking only when a teenage girl walks by, entering the ocean with cinder blocks tied to her body, meaning to commit suicide:

Joseph understands: the cinder blocks will hold her down and she will drown.

He lets his forehead back down against the sand. There is only the sound of waves collapsing against the shore and that starlight, faint and clean, reflecting off the mica in the sand. It is the same all over the world, Joseph thinks, in the smallest hours of the night. He wonders what would have happened if he had decided to sleep elsewhere, if he had spent one more hour framing trellises in the garden, if his seedlings had failed to shoot. If he had never seen an ad in a newspaper. If his mother had not gone to market that day. Order, chance, fate: it does not matter what brought him here. The stars burn in their constellations. Beneath the surface of the ocean countless lives are being lived out every minute.

He runs down the dunes and dives into the water.

In the version anthologized in Ben Marcus’s The Anchor Book of New American Stories, “The Caretaker” is 41 pages long. This passage happens on p. 23 or so, halfway through a scene just past the center point of the story. Even without having the rest of the story in front of you, can you feel the exquisite suspense of the pause between the two sentences flanking that middle paragraph?

Let’s break it down. We learn, alongside Joseph, that the girl is about to drown. Nine sentences pass, but only one beat of forward moving time occurs—that forehead hitting the sand—while Joseph hears the waves and sees the sunlight and remembers months of travel, out of Liberia, across the ocean to Oregon, then taking the job as the caretaker, losing that job, moving into the woods, planting a stolen garden, so on and so forth, a reminder to the reader of all the events which have brought him to this moment, all that history now gathered into the fist of this paragraph, held there as Doerr reaches up to the burning constellations and down into the depths of the ocean, moving the eye anywhere but the beach where Joseph is deciding what to do.

And then, in the next sentence, Joseph moves, time resumes, and a moment later the girl is saved: “He runs down the dunes and dives into the water… He dives under and lifts one of the cinder blocks from the sand and frees her wrist. With his arms beneath her body, dragging the other block, he hauls her onto the sand.”

This is suspense as interrupted suspension, exactly as Doerr described in his essay, plus summary as a way of gathering of an entire timeline into a single point, giving the scene increased gravity and importance. It is also a pause in the story’s rate of revelation, a paragraph where we learn only what he have already learn, before new knowledge once again begins to flow: “[The girl], Joseph realizes, is Twyman’s daughter.”

I want to offer one more quick example to show how this same tactic can be used as a structural unit of a novel, as opposed to a scene-level interruption. China Miéville’s New Weird fantasy novel The Scar is much too complicated to summarize both well and quickly, and so these quotes might be hard to read without context, but here’s the basic gist: The Scar is about a floating city called Armada, whose rulers (named The Lovers) set out to capture a mythical sea creature called the avanc in order to drag the city into a far-off dangerous ocean, where the titular “scar” awaits. Here’s a summary passsage detailing “the story so far,” from deep in the novel:

The avanc can take us to see what happened to the wound in the sea. That’s why it was summoned. That’s why Tintinnabulum was employed; and why the Sorghum was stolen for fuel; and why we went to the island and brought back Aum; and why you, Doul, have been working on a secret project, because of your sword, because of your expertise in this science. This is what everything leads to. This is why the avanc was summoned. It can cross the water that Armada would never breach without it.

It can cross that ocean.

It can take us to the Scar.

And then another, three pages later:

The scale of the project was staggering. The realization that all the misery and money and terrible effort that the Lovers had gone to to secure the avanc, the realization that that was only the first part of their plan, was incredible.

“All this,” breathed Silas, and Bellis nodded. “All of it,” she said.

“The rig, the Terpsichoria, Johannes, the anophelii island, the chains, the fulmen, the fucking avanc … all of it. This is what it’s about.”

“Naked power.” Silas mouthed it as if the words were dirty.

The Scar is 594 pages in my edition. These two excerpts are on pages 399 and 402: they are precisely two-thirds of the way through, and together they create a precipice from which the reader plunges into the third act of the book, a fulcrum of summary on which the novel momentarily balances before rushing toward its conclusion.

“A hero (and therefore also a reader) finds herself caught between two points and dangles there a while,” Doerr tells us—and don’t these two passages accomplish exactly that? In these moments, Miéville suspends us alongside his characters, leaving us with the exact same amount of knowledge of the past, the exact same trepidation—and then he pushes us all onward, characters and readers entering the future side by side.

Your exercise this month comes with two options, one generative and one for revision:

Exercise 1 (Generative): Write a 750-word flash fiction composed almost entirely of “the story so far,” with each sentence being a high-energy but summarized recounting of something that occurred before your story begins. Two exceptions: Put one beat of forward-moving time in the first sentence (as in the Doerr passage above), then don’t let time in the present move forward again until the story’s last sentence (or the last two or three). How much suspense can you make out of the past, as an interruption of the present? How can you powerfully propel yourself out of that interruption, toward your conclusion?

Exercise 2 (Revision): Look through a story or novel chapter you’ve already written, and find a place to insert a single paragraph of suspense-generating summary. Where in your story might such a paragraph do the most work? Climactic scenes and other kinds of turning points are the likely best places to try, but probably not the only ones that will serve you well. If all else fails, go to the two-thirds point of the novel or story and see what’s happening there: where is the turn to the end of your story, and what would happen if you forced the reader and the characters to pause there and reflect before plunging onward?

Good luck! See you next month!

Thanks so much for reading! If you’re not already subscribed, please consider doing so by clicking the button below. This post is also publicly accessible, so feel free to share!

Matt Bell’s next novel, Appleseed, is forthcoming from Custom House in July 2021. His craft book Refuse to Be Done, a guide to novel writing, rewriting, & revision, will follow in early 2022 from Soho Press. He’s also the author of the novels Scrapper and In the House upon the Dirt between the Lake and the Woods, as well as the short story collection A Tree or a Person or a Wall, a non-fiction book about the classic video game Baldur’s Gate II, and several other titles. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Tin House, Conjunctions, Fairy Tale Review, American Short Fiction, and many other publications. A native of Michigan, he teaches creative writing at Arizona State University.

A perfect lesson for my creative writing class after spring break. Thank you!