Exercise #21: How to Study Sentence Structure

Ursula K. Le Guin, Yan Ge, Lauren Redniss, Carmen Maria Machado, Denis Johnson, Michael Faber, Louise Erdrich, Joan Didion

Hi friends,

It’s the first week of September, and also somehow already the third week of my semester at ASU. I’m vaxxed and masked and teaching in-person for the first time since March of last year, and despite everything it’s been such a pleasure to be in the classroom again with my bright and interesting students. My class on worldbuilding in science fiction and fantasy has thirty-eight students in it, and it was a pleasure to hear so much enthusiasm and excitement in one room these past two weeks, as we kicked off our semester talking about Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness. (By coincidence, an essay I wrote about the craft lessons I learned from my year of reading as much of Le Guin’s body of work as I could came out last week at Tor, on the same day we started discussing the book.) I’m obviously worried about all that might go wrong, but it’s clear my students are as excited to be back in-person as I am, and I’m hoping to make the most of being there with them.

Otherwise, the work continues! I’m finishing copyedits on Refuse to Be Done this week, and then getting back into the draft of my next novel. Different versions of Refuse to Be Done have been boomeranging back to me as it’s gone through the editorial process, and so it’s been curious to experience reading my own advice about novel writing a few times as I try my best to write another.

I hope your own writing goes well this month, and that you and yours are happy and healthy. I know it’s a difficult time in so many ways right now, but I hope there’s solace and community wherever you are.

Enjoy this month’s exercise, be safe, be kind, and happy reading and writing!

Yours,

Matt

What I’m Reading:

Strange Beasts of China by Yan Ge (translated by Jeremy Tiang): I’ve got one more chapter to read in this novel still, but Yan Ge’s debut seems destined to be one of my favorite books of the year. Set in the fictional Chinese city of Yong'an, it follows a cryptozoologist/novelist who’s documenting the “beasts” who live among the people of her city, beasts that are both fantastical and deeply human. If you’ve been looking something beyond the usual speculative fare, I think this will do nicely.

Oak Flat: A Fight for Sacred Land in the American West by Lauren Redniss: This is the beginning of my eighth year in Arizona, but I’m still learning my way through both the history and the current issues of my new home state. Redniss’s Oak Flat is one of the best books I’ve read about the region in recent memory, and its telling of the conflict between the copper mining industry and the people of the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation over the future of the sacred natural land at Oak Flat is well worth a read, no matter where you live.

Exercise #21: How to Study Sentence Structure

I mentioned last month that I taught a few workshops on sentence acoustics and style this summer, finishing up in August right before I had to turn my attention to my university teaching. The conversations I had in those summer workshops are still on my mind, so I thought I’d offer one more exercise on the sentence before moving on to other topics next month.

Whenever I teach these workshops, I bring a PowerPoint loaded with one hundred slides worth of example sentences and short paragraphs that I think are particularly interesting in some way. As we work through some of the examples, we’re paying attention to how sound and rhythm and sense are created through word choice, punctuation, and grammar, in hopes of discovering what we’re drawn to at the level of the sentence, as well as how those effects work so that we might try them again in our own fiction. To do this, it helps to learn some vocabulary for talking about grammar and the poetics of language—words like alliteration, assonance, and consonance, and so on—because being able to name something precisely often makes it easier to see. But even without all that language, you can break down sentences you admire by paying attention to just two categories of words that necessarily appear in almost every sentence: content words and functional words.

Content words are the nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Functional words are the others you find arranged around them: prepositions, conjunctions, determiners, auxiliaries, and some pronouns. (For our purposes here, we’re going to begin by focusing on the former.)

One way to learn how to make your own sentence like the the ones you admire most is simply to re-use an existing sentence’s structure to your own ends, trying it on and seeing how it fits. One way you might go about this is by replacing the model sentence’s content words with new ones, an operation that sounds as simple as a mad lib, but gets tricky if your goal is to make something as good as the original. How can you retain the grammatical shape of the model sentence, while making it mean something else that’s equally as interesting to read and to hear?

Let’s begin by analyzing a fairly simple sentence I like from Carmen Maria Machado’s “The Husband Stitch”:

“Stories can sense happiness and snuff it out like a candle.”

Identifying the content words, we end up with something like this:

“[Noun] can [verb] [noun] and [verb] it like a [noun].”

If you swapped in your own content words here, what might you come up with? Give it a try quickly, before moving on. (You might find this hard to do off the top of your head: more on that below.)

Here’s a more complicated sentence, from Denis Johnson’s “Emergency”:

“We made love in the bed, ate steaks at the restaurant, shot up in the john, puked, cried, accused one another, begged of one another, forgave, promised, and carried one another to heaven.”

This one is made up of almost nothing but content words—in fact, I think it’s possible that the content-to-function word ratio is high in many good sentences:

“We [verb phrase] in the [noun], [verb] [noun] at the [noun], [verb phrase] in the [noun], [verb], [verb], [verb phrase], [verb phrase], [verb], [verb], and [verb phrase] to [noun].”

Now a sentence from Michael Faber’s Under the Skin, one that’s probably odd out of context but that has an interesting adjective pile-up:

“The thought of a shaved, castrated, fattened, intestinally modified, chemically purified vodsel turning up at a police station or a hospital was a nightmare made flesh.”

Breaking it down, it looks something like:

“The [noun] of a [adjective], [adjective], [adjective], [adverb] [adjective], [adverb] [adjective] [noun] [verb phrase] at a [noun] or a [noun] was a [noun] [verb] [noun].”

Another interesting example, from Louise Erdrich’s “The Flower,” this time with a verb pile-up creating the sentence’s left branch:

“Fighting, outwitting, burning, even leaving food behind for the head to gobble, just to slow it down, the girl, Wolfred, and the dog travelled.”

Which you might analyze like this—note that this time I made the preposition changeable, because it seemed to need to be swappable here:

"[Verb], [verb], [verb], even [verb] [noun] [preposition] for the [noun] to [verb], just to [verb phrase], the [noun], [proper noun], and the [noun] [verb].”

You might also try to mimic patterns of repetition, a particularly pleasing rhetorical strategy we can see in this sentence from Joan Didion’s Blue Nights:

“Memory fades, memory adjusts, memory conforms to what we think we remember.”

Which works something like:

“[Noun1] [verb 1], [noun1] [verb2], [noun1] [verb phrase].”

I could go on and on, but you get the idea. Note that the goal of this kind of analysis isn’t to beat yourself up about being grammatically correct in what you name everything: you might even already have quibbles with my quick attempts at breaking down the sentences above. Do your best, using the knowledge you have, and give yourself something to work with when it’s time to write. That’s really all this exercise requires.

Your exercise for this month is to take a favorite sentence or paragraph and then do your best to identify its content words. Afterward, write your own sentence or paragraph in which you swap in your own content words, changing the meaning of the sentence but preserving its grammatical structure.

Some guidelines:

The sentence you produce should make at least as much sense as the sentence you modeled yours on. It’s not hard to produce mad-libbed gibberish by this method, but such results should be avoided.

Try to end up with a sentence that’s also as acoustically interesting as the original. Many of the sentences above rely on repeated sounds and word resemblances; yours will likely need to do the same, but they will probably be different repetitions and resemblances than the model’s.

You will probably want to preserve the tenses of the verbs you replace, but I’m not sure that’s a hard and fast rule.

I mentioned above that it can be hard to figure out what content words to swap in, when working on a sentence in isolation. For that reason, you may find it easier to try to do this exercise inside an existing draft you’re working on. The sentence you produce by doing so may or may not immediately fit in the draft—the sentences above existed in a different context—but it may suggest interesting possibilities to you by its “wrongness” too.

Obviously, work the above exercise only until it stops being useful. If the sentence you’re building from a model wants to go another, better direction, follow it! This is part of how the sentence will move from imitation toward inspiration and influence.

You could, of course, go beyond doing this with a paragraph and do it with a whole flash fiction or scene. (If you were feeling particularly Oulipian, you could do it with a whole book…)

It goes without saying (but I’ll say it anyway), that you’ll want to give credit where credit is due with this kind of thing, as appropriate.

Have fun with this! This is one way of learning how your favorite sentences and paragraphs are actually built, and it’s something I personally do often when I encounter a particularly interesting piece of prose. I want to always be increasing the number of tools at my disposal, and this is one way I set out to do so. I hope it’s as useful an exercise for you as it is for me.

Good luck! See you next month!

Thanks so much for reading! If you’re not already subscribed, please consider doing so by clicking the button below. This post is also publicly accessible, so feel free to share!

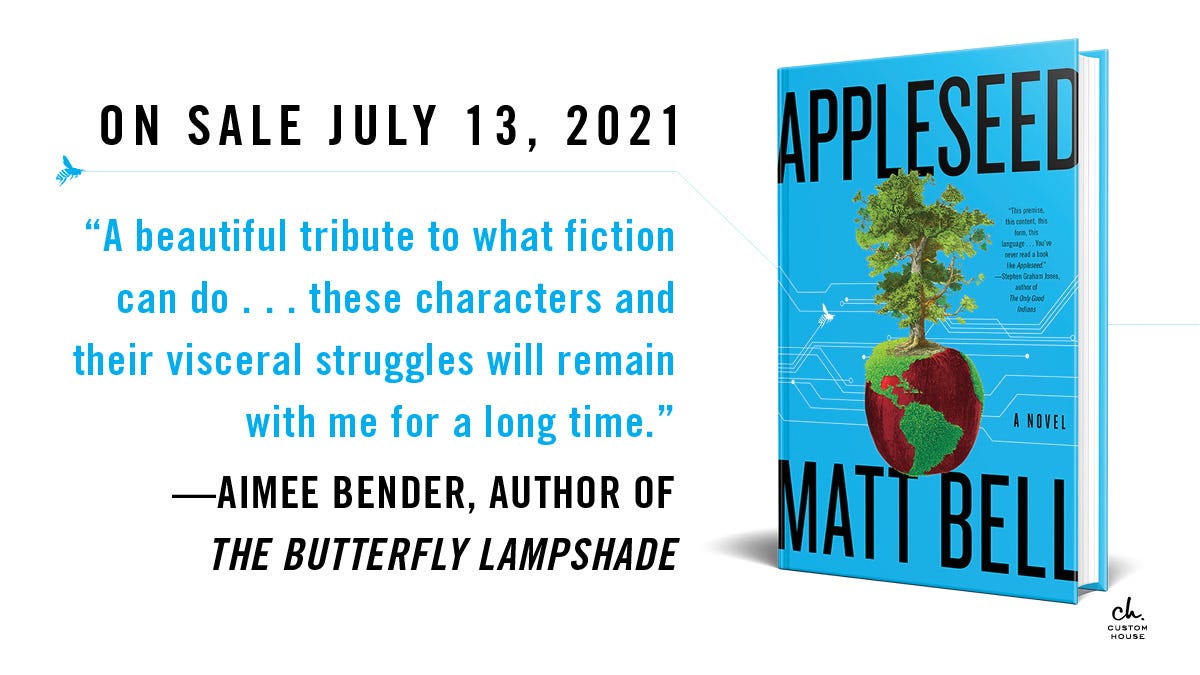

Matt Bell’s novel Appleseed was published Custom House in July 2021. His craft book Refuse to Be Done, a guide to novel writing, rewriting, & revision, will follow in March 2022 from Soho Press. He’s also the author of the novels Scrapper and In the House upon the Dirt between the Lake and the Woods, as well as the short story collection A Tree or a Person or a Wall, a non-fiction book about the classic video game Baldur’s Gate II, and several other titles. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Tin House, Conjunctions, Fairy Tale Review, American Short Fiction, and many other publications. A native of Michigan, he teaches creative writing at Arizona State University.

Love this exercise, Matt! Thank you for sharing. Would that PPT be available too? Or is that something that you prefer to not push out to the public?