Exercise #23: Activating Backstory with Dialogue Instead of Flashbacks and Info Dumps

Laird Hunt, Mike Meginnis, Alexandra Kleeman, Mary Gaitskill

Hi friends,

I’m writing this from Phoenix on October 30, but if all goes well it’ll actually reach you as I’m landing in France on November 1. This is my first significant travel since before the pandemic started, and a trip that’s been delayed more than once already: I was supposed to go in November 2020, then January 2021, but both times Covid made it impossible to travel to the EU. This time around travel should hopefully more smoothly, allowing me to finally take advantage of a month-long writing residency I’ve been offered, where I’m hoping to make significant progress toward finishing the draft of my next novel. Fingers crossed for easy travel and productive writing sessions: next month’s newsletter will come to you from France too, as the residency comes to an end.

Also: Advance review copies of Refuse to Be Done are in! If you’re a book reviewer interested in covering it or a creative writing teacher interested in considering the book for a future class, you can email my publicist Erica Loberg at Soho Press, or request a digital copy directly through Edelweiss or NetGalley. Otherwise, it’ll be out in just a few short months on March 22, 2022, and is available for preorder now. (Thanks to everyone who’s already reserved their copy!)

As always, I hope your own writing goes well this month, and that you and yours are happy and healthy. Enjoy this month’s exercise, be safe, be kind, and happy reading and writing!

Yours,

Matt

What I’m Reading:

Zorrie by Laird Hunt: Laird Hunt has been one of my favorite writers for as long as I’ve known about him, but his 2012 novel Kind One felt like a jump to a new level in his work. Including that novel, he’s written five innovative, complex, and beautifully written historical novels in nine years, each of which I’ve loved: Zorrie, his latest, is another fantastic read. I’m so glad it’s a finalist for the National Book Award this year, and I’m cheering for it and for Laird. In my opinion, there’s almost no one who’s had a better or more accomplished decade as a writer.

Drowning Practice by Mike Meginnis: I read Mike Meginnis’s forthcoming novel Drowning Practice to write a blurb for it, which I gladly did, but I would have begged for a copy if I hadn’t been asked. Ten years ago, Meginnis wrote a story called “Navigators” for Hobart that remains one of my favorite stories ever, and I believe Drowning Practice is going to be equally unforgettable. This is out next March, so I won’t spoil anything about it, but I will recommend you preorder it now. You won’t want to miss it.

Exercise #23: Activating Backstory with Dialogue Instead of Flashbacks and Info Dumps

For almost as long as I’ve been writing, I’ve been suspicious of novels or stories with an overabundance of backstory presented in flashbacks and exposition. My objections are all the usual ones: if the backstory is overwhelming the present, it begins to seem like maybe the backstory is the real story, and the present action should be set there instead; if the backstory is rendered in scenes (especially set off in their own chapters) then there’s often a lot of corresponding narrative drag, because the writer has to constantly rebuild momentum as the reader comes out of the flashbacks back into the present. There’s also the risk of making the action of the present narrative a mere psychological outcome of the past: if the character does what they do for some reason corresponding too neatly to their past traumas or experiences, the resulting plot feels cheaply predetermined, robbing the protagonist of agency.

All that said, the past does obviously influence the present in fiction (as in life), including in the stories characters tell about who they are and how they became that person, a kind of self-mythologizing that almost everyone does to some extent. Each of us has our own idea about which past experiences made us who we are today—although whether we are right about this is another thing entirely—and often we continue to enact those past stories in our present lives. So how do we mimic this in fiction, without creating too much drag on our plot or cheapening our characters’ psychology?

For me, the best way to do this is to avoid flashback scenes and expositional info dumps as much as possible, preferring wherever possible to instead let characters tell their stories in dialogue or at least in active in-scene thought, with a strong priority given to the first.

Why do I think backstory is strongest in dialogue? Because dialogue is an interaction between two characters, instead of mere information delivery to the reader. A story told to someone else has a purpose above and beyond its mere content: it is meant to entertain, to entice, to persuade or compel or accuse another character. As such, the backstory becomes not just information about the speaker but the active material of the fiction’s present narrative, an interaction that creates discoveries and complications and producing changes in the relationships between characters.

I started thinking about this again while reading Alexandra Kleeman’s latest novel Something New Under the Sun, an excellent noirish climate change novel set in Hollywood in the near future. Its protagonist is Patrick Hamlin, a novelist from the East Coast who’s come to California to participate in the adaptation of one of his novels; his primary relationship in the book’s present is with Cassidy Carter, the disgraced former child star who’s starring in the movie. As the novel opens, Patrick knows Cassidy only by reputation, by what appears in the news, in online videos of her recent public misbehavior, and in the episodes of her childhood TV show he streams. It’s only once they two of them begin spending time together (after Patrick becomes her chauffeur to and from the movie set) that he begins to learn more about her past.

Elsinore Lane, the novel of Patrick’s being adapted, was a literary ghost story (a surrealist telling of his relationship with his father) that is now being made into a more straightforward horror novel, much to Patrick’s chagrin. As he finally reads the script, he reflects on his relationship with his parents and the choices he made in fictionalizing them:

Patrick sometimes wondered if he had chosen to turn his father into a ghost in the novel, an absent figure appearing in visions to the son and gesturing or mouthing words he could not speak, in order to avoid having to make up a character for him to be. Patrick hated the convention of flashback and backstory as a way to pretend that characters were deeper and richer than they appeared to be in the moment—but if he hadn’t hated the convention, he might have included more of his own memories of his father, most of which were ambient and cyclical, things his father tended to do rather than specific things his father had done.

Patrick hated the convention of flashback and backstory as a way to pretend that characters were deeper and richer than they appeared to be in the moment, Kleeman writes—and reading that, I immediately thought, Patrick and I both agree on this, and also maybe suffer from some of the same problems as a result. But of course this note occurs in a backstory-revealing passage where Patrick is thinking mostly to himself—it is on some level the very thing Patrick thinks he disdains.

Backstory is important to Something New Under the Sun, but most often it appears not in exposition or direct thought but in dialogue. (There are very few pure flashbacks, if any, in my recollection.) One of my favorite bits of backstory in the novel is Cassidy Carter’s story about how and why she came to Hollywood, which is presented entirely in dialogue as Cassidy is being driven around, arguing with Patrick. The two characters are at a breaking point in their relationship, where Patrick resents being saddled with Cassidy, and where Cassidy is generally unimpressed by Patrick’s contribution to their movie and his lackluster chauffeuring of her.

It’s a long quote, but I think it’s worth your seeing exactly how Cassidy’s backstory plays out when presented in dialogue:

“I was a kid,” Cassidy says, facing away from [Patrick], staring out. “I came from the most Podunk town you’ve never heard of. We were famous for growing hay. People don’t even eat hay. And it’s not that my town was the best place to grow hay, we just made a lot of it. In the fall, hay rides and hay mazes. Scarecrows and pumpkins. The smell of living stuff drying out in the sun, geraniums in the front yard. Whatever.”

She looks at Patrick and then back out at the canyon in motion.

“This was inland, an hour from Fresno. Four or five hours from here. Nothing ever happened there, not even a hit-and-run. There just weren’t enough people. And then, one day, I’m walking back from where the school bus used to let me off and this amazing car pulls up. I didn’t even know what kind of car it was; probably it was some pretty humdrum bullshit, but it was shiny, and the roof was down. And inside that car was Rainer Westchapel. Do you remember him?”

Patrick reluctantly shakes his head no.

“He was in that Christmas movie, the one where Santa gives all the good children coal and all the bad children ponies by accident and one man, an ordinary IRS clerk, has to set it all straight. Even Santa Makes Mistakes, that movie. Well, Rainer Westchapel played the IRS guy’s best friend, the abstract painter with the wise advice. I know you’ve seen it. They show it every year.”

“Maybe,” says Patrick. “I wouldn’t know.”

“So Rainer Westchapel pulls up next to me, and he’s lost, he was trying to get to some hot spring where his buddy had a vacation house. He was house-sitting. He’s not so famous, you’d only know him from Even Santa Makes Mistakes. But he was the biggest celebrity ever to pass through Haywood, and I got to give him directions back to the highway. Personally. It was a catastrophe for me, like a tornado or a hurricane. It changed everything. I felt like I had been diagnosed with leukemia, like one of those kids on TV where there’s a number you’re supposed to call to donate. I literally couldn’t stay in a town where there was no chance that I’d ever see another celebrity ever again. It hurt, to think that my life would be Rainer Westchapel asking for directions, and then decade after decade of nothing, and then death. Death was right in front of me. I finally convinced my mom to move June and me closer to L.A. so that I could do auditions. It wasn’t that hard; my dad had already left us.”

There’s a little more to Cassidy’s story after this, but I think by now you get the gist: this is Cassidy Carter’s origin story, why she started down the path from a girl from “the most Podunk town” to a future child star. It also contains a good chunk of her family history, presented subtly and almost as an aside: that last line about Cassidy’s father leaving her family when she was young, an important personal detail tossed off with a shrug.

All of this backstory is delivered in Cassidy’s own voice, filtered through her personality and spoken in response to the interpersonal demands of the scene; as such, it not only reveals something about her character to the reader and to Patrick, but it also creates change in her relationship with Patrick. In a lesser novel, the entire encounter with Rainer Westchapel could have been presented as a more fully realized scene, in a chapter or a section of its own—but it would not be improved by doing so.

Standing alone, in scene, this bit of Cassidy’s backstory would be informative, but only to the reader: Cassidy already knows this, and Patrick still wouldn’t. But presented here, in scene, it emerges from the demands of the present narrative, affects the character relationships in play, and still gives the reader new information with which to interpret Cassidy’s actions in the novel. As dialogue, it also muddies the objectiveness of the backstory information: a standalone scene would more likely be read as absolute truth, while in dialogue the events of the past are clearly being interpreted by Cassidy’s consciousness and her desire for how she wants to see herself, how she wants others to see her.

For me, backstory revealed by dialogue is a much richer, more dynamic way to get the past onto the page, and Kleeman’s book is a great place to study how it can be done well. In a third person novel like Something New Under the Sun, this tactic also frees the backstory from the influence of the narratorial perspective, ceding control of detail selection and pacing to the character instead.

These same tactics work for worldbuilding information too: by revealing the details of an invented world through dialogue, you also attach your characters’ in-world opinions to them, again muddying their objective reality for something more subjective. This puts the details into play as part of the novel’s story, as opposed to merely being static “facts” about the novel’s setting.

Your exercise this month is to write a scene in which a character reveals an important moment from their past in dialogue with at least one other character. Crucially, the backstory revealed should have a purpose in the scene, on top of what it reveals about the past; it should also be filtered through the character’s personality and their aims in the moment.

A few suggestions that might help you achieve the intended effect:

1) Do not use any other tactic but dialogue to reveal the past: no interior monologues, no exposition, no other narratorial interruptions.

2) Do use every kind of dialogue available to you, as you like: direct dialogue is the most obvious choice, as in the Kleeman example above, but don’t forget that you also have the tools of indirect and summarized dialogue at your disposal as well.

3) Don’t bail on the backstory reveal until its being revealed creates some change in the present. Does it convince the listener to take action or to feel differently? Does it recast the relationship between speaker and the listener? How are their positions shifted by the telling?

Note that you can do this by writing a new story centered around this telling, or you could take a chunk of backstory from an existing story or novel chapter and recast it using the above tactics. Either works! I frequently find the opportunities for these kinds of moments in my work only in revision—and they often feel very obvious to me in other people’s drafts. The potential for this is one of the things I might ask a beta reader to look out for in my drafts, to help me make the next draft more dynamic.

Good luck! See you next month!

P.S. I focused on dialogue above, but if you want to study how to reveal backstory by a character actively thinking in-scene about the past, check out Mary Gaitskill’s story “Tiny Smiling Daddy”: it’s extraordinary. I return often to this story to study how Gaitskill made her narrator’s backstory so dynamic and complex and active in the present.

Thanks so much for reading! If you’re not already subscribed, please consider doing so by clicking the button below. This post is also publicly accessible, so feel free to share!

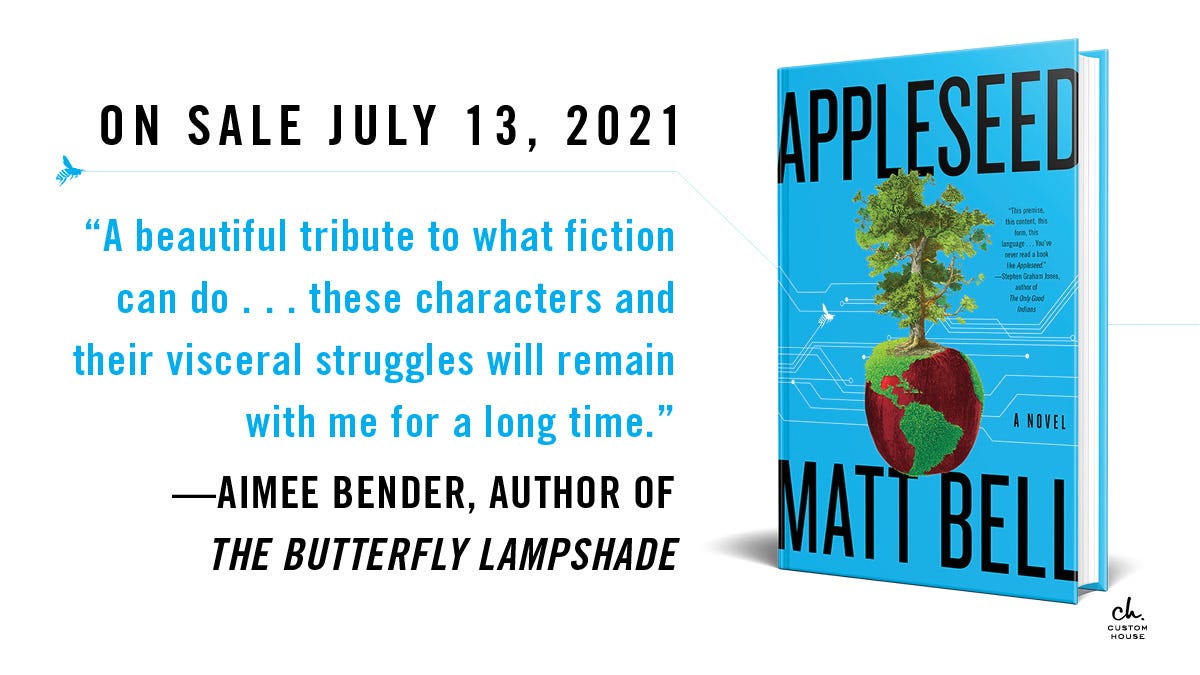

Matt Bell’s novel Appleseed was published Custom House in July 2021. His craft book Refuse to Be Done, a guide to novel writing, rewriting, & revision, will follow in March 2022 from Soho Press. He’s also the author of the novels Scrapper and In the House upon the Dirt between the Lake and the Woods, as well as the short story collection A Tree or a Person or a Wall, a non-fiction book about the classic video game Baldur’s Gate II, and several other titles. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Tin House, Conjunctions, Fairy Tale Review, American Short Fiction, and many other publications. A native of Michigan, he teaches creative writing at Arizona State University.

I can't wait to try this in my revisions for my current WIP. I'm taking a break after finishing my first draft, but this sounds like a really great way to "revise out" some backstory.

Mind Blown! LOVE this exercise. And love love that book cover, holy cow. My hand reacted as I scanned top to bottom, from the crumpled to the smooth. Thank you thank you.