Exercise #34: The Annotated Debut

Stephen King, Megan Giddings, Jonathan Franzen, Douglas Adams

Hi friends,

I hope the end of your summer is going well! My semester is three weeks old already, and thankfully feels off to a good start. I think this is the most normal the vibe on campus has felt since COVID began in 2020, and it’s been a pleasure to be surrounded by so much student excitement and talent. This month’s exercise is a version of an assignment I recently gave to my undergrad capstone students as part of a lesson on publishing and literary careers: it’s a little different than what I usually write for this newsletter, but I hope it’s useful: I think it’s a particularly illuminating exercise, especially for writers who haven’t yet published a first book.

This week, I also had the pleasure of reviewing Stephen King’s new novel Fairy Tale for the New York Times Book Review! The quick version: I enjoyed the hell out of it, and I think it's going to land well especially with the Dark Tower/The Talisman/Eyes of the Dragon end of his readership. (As long-time subscribers may recall, I reread the Dark Tower series in its entirety in 2020, which turned out to be good prep for this assignment.) If you’re a fan of any of King’s fantasy novels, my guess is you’ll like this one too.

It’s a ways out still, but on November 19, I’ll be teaching a three-hour online class on “Worldbuilding Tactics for Science Fiction and Fantasy” for my friends at the Writers’ League of Texas. Spots are limited, so register early if you’re interested!

As always, I hope your writing is going well, and that you and yours are happy and healthy. Be safe, be kind, and have fun with your reading and writing!

Yours,

Matt

What I’m Reading:

The Women Could Fly by Megan Giddings. I loved Giddings’s debut Lakewood, and I think The Women Could Fly is even better. Set in a contemporary world where women’s lives are bounded and policed by omnipresent claims of witchcraft, the best part of the novel takes place on a secretive island hidden in the Great Lakes where women practice “forbidden” magic in community and collaboration.

Crossroads by Jonathan Franzen. I enjoyed this novel more than anything else of Franzen’s that I’ve read, maybe in part because it’s about some of my own interests/experiences, like Midwestern youth group culture. (It also depicts a kind of moralized overthinking that feels very familiar to me, in ways I find both honest and often horrific.) A number of people whose opinions I respect said this was their favorite Franzen, and it turns out it’s mine too.

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams. I turned 42 a couple days ago, and what else could I read on my birthday but this? I loved this book so much when I was kid, and its pleasures have held up well over time. A delight to reread this favorite.

Exercise #34: The Annotated Debut

I’m a big believer in positive visualization, and have been since I was a kid, when my godfather taught it to me as a way of psyching myself up for wrestling matches: to picture the steps of winning was to prepare to win. As a trail runner, I frequently picture myself on the course of an upcoming race, imagining how I might flow over the landscape; as a writer, I imagine the future cover of the book I’m writing or how it will feel to hold the final copy or even just what the table of contents might look like, once I’ve filled it in. I prep for teaching partly by imagining what it’ll be like to be in the classroom, giving the lesson I’m planning. To do this, I need to know the steps that will lead to a task’s success or at least its completion: the more I know about the turns and hills of a race, for instance, the easier it is to imagine my way through the course.

For most of my students—and for many of the aspiring writers I’ve met—it’s hard to do this kind of planning and visualization in regards to the publishing of a book, because the intermediary steps between us and our goals are unclear. How do we go from being unpublished writers to the authors of books? What are the possible actions along the way? How will we know when we’re ready, or when our aspirations are plausible? What concrete moves can we make to make progress? Should we study more? If so, who should we study with? Do we need to publish stories before we can publish novels? If so, where can we publish them? What kind of fellowships or residencies might we try to win in the early, pre-book part of our career? Do we need any or all of these things to happen before we can get an agent or publish a novel?

Everyone reading this probably knows there’s no one right solution to the puzzle of building a literary career. But everyone who publishes a first book found some answer.

Here’s an example from how I found mine: I started writing fiction with short stories, which also meant I read plenty of short story collections. One thing I learned to pay attention to was the copyright pages or the book’s acknowledgments, wherever the writer listed the magazines who’d previously published the book’s individual stories. This was one of the ways I decided which literary magazines to subscribe to, and it also helped me decide where to submit my own work: if I read a collection whose aesthetics seemed aligned with mine, I would read and then submit to the literary magazines who’d published its stories. I had a lot of success with this tactic, especially when the books were fairly recent, because the more recent the collection, the more likely it was that the magazines still had the same editors or aesthetics.

I still always read a writer’s acknowledgments, sometimes before I’ve finished the book. This started out as simply indulging my curiosity, affording me a glimpse into a writer’s life that’s more personal or detailed than the bio on their book jacket—but eventually I realized there was a lot to learn here too. Most writers thank at least their editors and agents, which means it’s possible, from reading lots of acknowledgments, to get an idea of which editors and agents are interested in what kinds of books. But many writers also go on to thank their classmates and writers’ groups (which are often a mix of published and unpublished authors), the people they met at writer’s conferences and residencies, the teachers they had in MFA programs or at Clarion or Cave Canem or Kundiman. They also necessarily thank institutions and organizations that gave them support: the National Endowment for the Arts, state and local arts boards, residency centers big and small.

Acknowledgments are getting longer and longer all the time, and debut writers usually have the longest ones: I’ve been reading a lot of debut fiction this summer, and many of them have acknowledgments sections that are three or four pages long. (I read at least one book that had six or seven pages of acknowledgments, a new record from what I’ve seen.) Because it’s their first chance to do so, these writers often thank everyone. In doing so they make visible the village that it often takes to produce a single book, full of people both inside the publishing industry and without. (One of the good things many people are doing, including me, is to try to thank more people inside their publisher, including juniors or assistant editors, production staff, designers, publicists, and so on, all of whom are generally less visible from the outside but do much of the work of making a book succeed.)

Now that acknowledgements have gotten so detailed, we can put all the information they offer to use. If you’re a writer unsure what next steps might get you where you want to go, try this:

Your exercise for this month is to annotate the bio, blurbs, and acknowledgements of a debut novel or short story collection published within the past three years, in the same genre that you write in. (Please note that for this to work correctly you’ll need the first printing of the book you choose, either the hardcover or a paperback original. If you use a later edition, the results will be skewed by post-publication reviews, awards, etc.)

Once you’ve chosen your book, copy every name, publication, organization, award, university, and other items listed in any of the above places into a list, then research each item in turn, writing at least a single sentence about what you find. Who are these people? How are they connected to the writer? (For instance, are the blurbers the writer’s former teachers?) Where did this person publish their first stories or early chapters of the novel? What are these organizations that supported this author, and how might you get them to help you too?

The purpose of this is to try to get a snapshot of one writer’s path to first book publication. What do you see in this person's example? What does it suggest you might need to do to publish your own first book in your particular genre? Are any of the things that helped your writer possible to apply for or chase after in your own life? Not everything will be a task or a checklist item! Look for opportunities especially for potential support, such as fellowships and residencies; assume that the magazines that published other writers before their first books came out might also do the same for you.

Remember that everything you find in a debut’s acknowledgments is by definition something that was somehow available to a writer who had not yet published a book. Everyone’s career is different, but what’s listed in a debut’s acknowledgments are someone’s early career opportunities—and they might give an idea how to plot your own path toward the goals you have for your books and your career. The more you can see the possible intermediary steps along the journey to the first book—while always remembering that there is no one right way—the easier it’ll be to visualize your future success.

Good luck! See you next month!

P.S. One memorable data point from this exercise: the last time I taught it, every big press story collection students brought in had at least one story published in Granta. What does that mean? Probably nothing! But it did suggest that writers who had not yet published a book could get serious attention at Granta—and that a Granta credit might get the attention of agents and big press editors. Who knows? Maybe it’s just a coincidence. But if I was starting out again, I’d now be trying to get into Granta.

P.P.S. This year, the new surprise this exercise unearthed was the first novel I’ve had a student bring in whose author’s path to publication seemed to have run entirely through successfully building a platform on BookTube. Their credibility as an author, their initial audience, and their blurbs, all originated from their work there. To me, that path seems even more daunting than the Granta one.

Thanks so much for reading! If you’re not already subscribed, please consider doing so by clicking the button below. This post is also publicly accessible, so feel free to share!

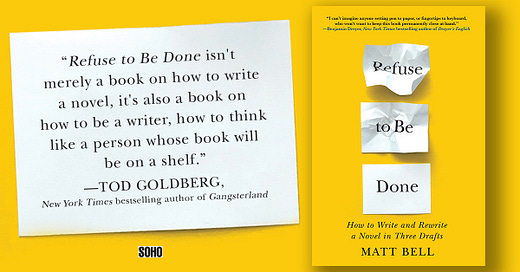

Matt Bell’s novel Appleseed was published by HarperCollins in July 2021. His craft book Refuse to Be Done, a guide to novel writing, rewriting, & revision, is out now from Soho Press. He’s also the author of the novels Scrapper and In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods, as well as the short story collection A Tree or a Person or a Wall, a non-fiction book about the classic video game Baldur’s Gate II, and several other titles. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Esquire, Tin House, Conjunctions, Fairy Tale Review, American Short Fiction, and many other publications. A native of Michigan, he teaches creative writing at Arizona State University.

This was awesome, Matt. Your story about your grandfather really hit me. When I was a kid in Little League, my dad taught me positive visualization to get better at hitting a baseball. I never got any better at hitting, but I adopted the visualization techniques to all stages of my screenwriting career and now into my path as a new(ish) fiction writer. I'm a bit older than you, but I wonder if there was something about that generation when we were kids, where people were learning positive visualization and passing it on. Thanks so much for sharing!

So refreshing to see an practical, meaningful, original exercise that could truly advance the ball for a writer. Well done!