REFUSE TO BE DONE Launch Day! / Exercise #28: Mapping the First Draft

Jane Alison, Matthew Salesses, Blake Snyder, Philip Gerard, Ann Leckie, Alix E. Harrow, N.K. Jemisin, David Mitchell, Lance Olsen, Mark Twain, Cormac McCarthy.

Hi friends,

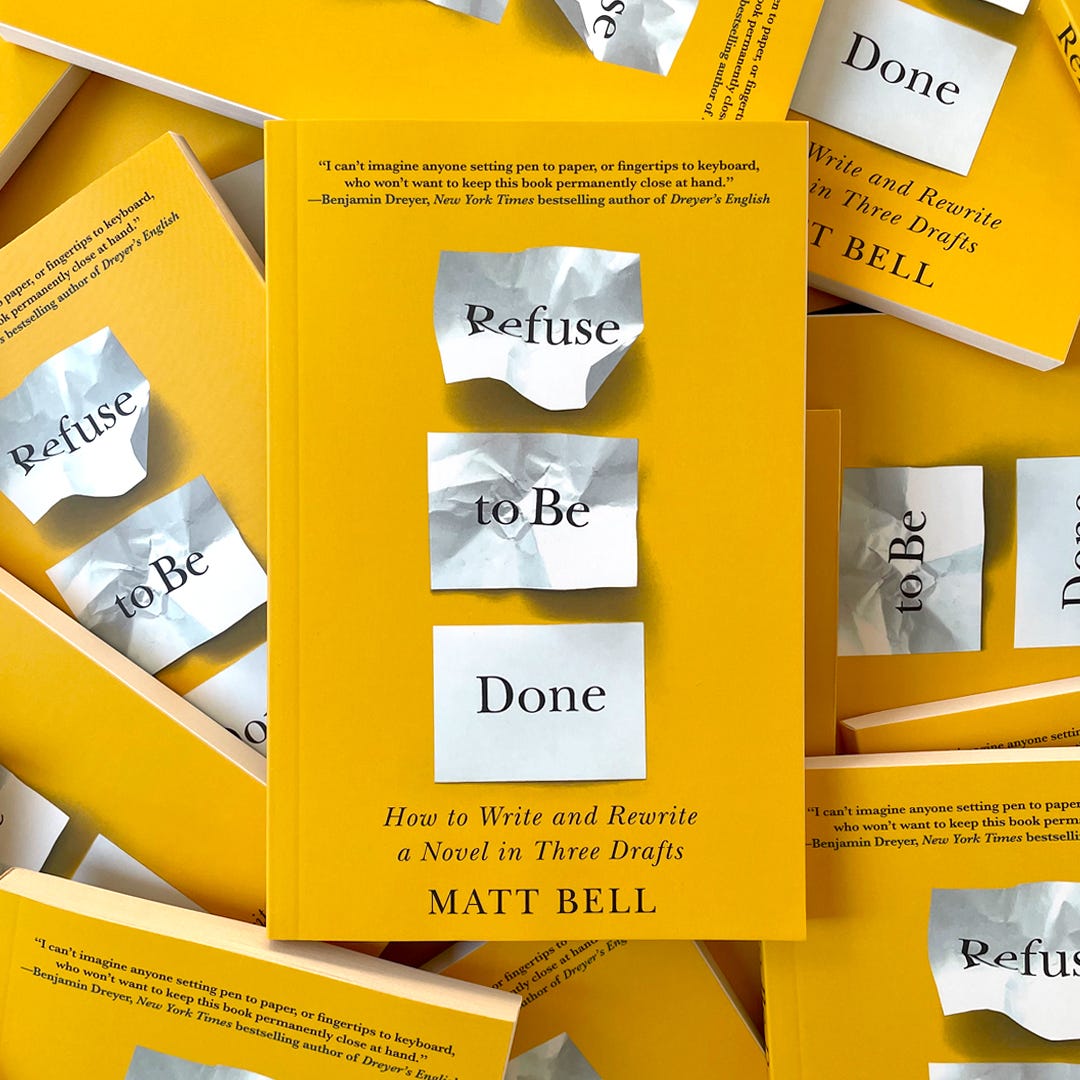

Today’s the day: my craft book Refuse to Be Done: How to Write and Rewrite a Novel in Three Drafts is now available! It’s an encouraging and practical guide to writing a novel and especially to revising and rewriting one, rooted in my own process and in what I’ve learned about the processes of others, as well as ten years of teaching novel writing workshops in my MFA program and elsewhere. Throughout the book, I advocate for an action-oriented approach, offering you many clear activities and next steps for every phase of novel writing, as well as ways to stay excited and invested. (And though I say novel, I hope the book will also be useful for people writing memoirs, creative nonfiction, and short stories: I use many of these tactics in almost everything I write, including my criticism.)

If you’ve already ordered your copy or are picking it up from your local indie, thank you so much: I hope it helps you finish the novel you’re writing! If you’d like to sample the book first, an excerpt was published yesterday at Lit Hub, about how you might approach the exploratory, generative, playful work of your first draft.

Refuse to Be Done was written before I began this newsletter, and very little of what’s in the book has been repeated here. But this space will now give me a chance to occasionally expand on what’s included, as I do in the exercise below explaining how I map a first draft to plan my second. It’s a step Refuse to Be Done describes too, but in less detail, so it might be worth returning to this newsletter to consider your options after you’ve read that part of the book.

As I said last time, I’ve got a mix of in-person and virtual events coming up, in both conversational and interactive lecture formats. Hopefully I’ll see some of you one place or another! Here’s the schedule so far:

March 8, 7pm ET, virtual: “Writing, Revising, and Editing Your Story,” a panel at CityLit Festival with Melissa Febos, Dean Smith, and Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai, moderated by Aditya Desai.

March 12, 6pm ET, in-person: “Workshop: The 3-Draft Novel” at the Tucson Festival of Books, Tucson, AZ

March 18, 4pm ET, virtual: “Friday Frontliner” at A Mighty Blaze, with Caroline Leavitt

March 19, 11am ET, virtual: Refuse to Be Done craft lecture at the Writer’s League of Texas (book included with registration)

March 22, 7pm ET, in-person/livestreamed: Book launch at the Center for Fiction, Brooklyn, NY, with Benjamin Dreyer

March 23, in-person: Refuse to Be Done craft lecture at Porter Square Books, Boston, MA, hosted by Grub Street (book included with registration)

March 31, 7pm ET, virtual: Craft Chat at The Writer's Center, Bethesda, MD, with Zach Powers

April 1, virtual: Refuse to Be Done craft lecture at Tin House (book included with registration)

April 2, in-person, 6pm: Refuse to Be Done craft lecture at Changing Hands, Phoenix, AZ (book included with paid registration)

April 7, virtual, 7pm ET: Norwich Bookstore, Norwich, VT, with Melanie Finn

April 8, virtual, 7:30pm ET: Refuse to be Done craft lecture at Charis Books, Atlanta, GA, co-hosted by Lostintheletters, with Scott Daughtridge (book included with registration)

April 14, virtual, 8pm ET: Mystery to Me, Madison, WI, with Michelle Wildgen

April 22, in-person: Lighthouse Writers Workshop Book Project Intensive

April 25, virtual, 6pm ET: Refuse to Be Done craft lecture at Writing Workshops Dallas (book included with registration)

April 28, virtual, 10pm ET: Refuse to Be Done craft lecture at Hugo House/Third Place Books (book included with registration)

May 2, virtual, 9pm ET: City Lights Bookstore, San Francisco, CA, with Kirstin Chen and Jac Jemc

May 10, virtual, 7pm ET: Refuse to Be Done craft lecture at Literary Cleveland (book included with registration)

May 23, virtual, 8pm ET: Refuse to Be Done craft lecture at StoryStudio Chicago (book included with registration)

Note that if a link isn’t available above, that means it’s not live yet with the hosting organization. I’ll come back and update this post as I get more info, or you can watch the events page at my website.

As always, I hope your writing is going well, and that you and yours are happy and healthy. Be safe, be kind, and have fun with your reading and writing!

Yours,

Matt

Exercise #28: Mapping the First Draft

One of the most important craft discoveries I made while writing my first novel In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods was when and how it was most useful for me to outline. (This won’t be the same for everyone!) Before that novel, I had always worried that an outline would hem me in unnecessarily and too early, because I like to write very exploratory first drafts, following threads and digressions and backstory I know probably won’t be there in the final draft but that nonetheless help me build out the hidden part of the novel’s “iceberg.”

So I wrote my first draft without much of a plan—sometimes I was even explicitly anti-planning—but then, once that draft was done, I decided to go ahead and make an outline of what I’d written as a way of “mapping” the story. This allowed me to see what was there, what was missing, and what needed to be rearranged.

To do this, I first wrote a “beat sheet,” trying to capture just the action of the time narrated, what actually happens in the primary timeline of the book. Then I revised that outline to make a plan for writing the second draft, trying to shape all that messy, exploratory material into a stronger structure and a more pleasing plot.

There’s a good description of this process in Refuse to Be Done, but one thing my book kind of skims over is where to find models to help you design this stronger structure or more pleasurable plot. How do you know what shape your material should take, when it’s not immediately obvious?

(It’s usually not immediately obvious.)

One way to find out is to try to fit your material to existing successful shapes: the three-act structure, the braided narrative, the serial or episodic plot, and/or Freytag’s Pyramid, among others. Basically, any existing structure will do: you use the bones of the known structure as a skeleton upon which to hang your scenes, then you see what parts are left bare. Maybe that’s material you need to write. Maybe something’s in the wrong place. Or maybe you’ve got too much of something: a hundred pages of opening exposition before the inciting incident, for instance. That’s solvable too.

Probably whatever structure you pick won’t fit your novel exactly. You can move your novel outline toward it—or you can try different structures until you find something more optimal for what you’ve already made.

My examples below focus on some of the most common structures novels take, but of course there are many successful shapes you might try: of recent craft books I’ve read, I’d suggest Jane Alison’s Meander Spiral Explode and Matthew Salesses’s Craft in the Real World as places to explore some of the alternatives.

The Three-Act Structure

I’ve been hearing about three-act structures for as long as I’m been writing, but a few years ago I realized I didn’t know exactly what went into each act: What do they entail? Where do you break from one to the other? Mostly when I heard other fiction writers talk about it, I didn’t think they totally knew either: everything we said was vague, gestural, incomplete.

Thankfully, screenwriters have written plenty of good guides to this structure, some more formulaic than others. But for the purposes of mapping a novel draft, the clarity of rigid formula becomes useful, especially as a start point. Let’s take a look at the three-act structure detailed in Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat, which goes so far as to tell exactly what page of a 110-page movie script each stage should happen on:

Opening Image (1)

Theme Stated (5)

Set-Up (1-10)

Catalyst (12)

Debate (12-25)

Break into Two (25)

B Story (30)

Fun and Games (30-55)

Midpoint (55)

Bad Guys Close In (55-75)

All Is Lost (75)

Dark Night of the Soul (75-85)

Break into Three (85)

Finale (85-110)

Final Image (110)

Most of these beats are easy to imagine, but it’s worth popping over to Snyder’s website or grabbing his book if you’re planning on trying this one out. Obviously, you’ve got to adjust the proportions a bit to make this work for a novel, but multiply Snyder’s page counts by three and you’ll get a general sense of where to put what in a typical 300-page novel.

I used Snyder’s structure to map the first draft of the novel I’m writing now, and it was immediately obvious to me that my proportions were off, and that my act breaks weren’t very clear. So I imagined new scenes that might fix that, and also did a lot of work trying to get existing scenes to do double (or triple) work so that the story could move along faster, especially in the early going. That was hugely helpful—even if in the actual next draft I’ve departed quite a bit from the formula above.

One place I might suggest you focus your attention here is on the “break into act two,” where I think this note from Philip Gerard might be useful:

“The act break is the moment where we leave the old world, the thesis statement, behind and proceed into a world that is the upside-down version of that, its antithesis. But because these worlds are so distinct, the act of actually stepping into Act Two must be very definite… The hero cannot be lured, tricked, or drift into Act Two. The hero must make the decision himself. That’s what makes him a hero—being proactive.”

That “break into act two” is very frequently something that’s not clear enough in a first draft: using this mapping tactic to find and strengthen that moment will do a lot of work for the effectiveness of your plot.

The Braided Narrative

My novel Appleseed has three storylines which stay in their own lanes for much of the book before intersecting in the third act. (It is, in my mind, both a braided narrative and a three-act structure: these different models don’t have to be mutually exclusive!) When I did my novel mapping, I treated each storyline as its own novel first, then later had to assemble them into a cohesive whole. But I didn’t have a particular model for how that braiding would work, and it wasn’t until after I was done that I found a clear example of braiding that I particularly liked, one that seems to crop up over and over again in good books I’ve read the past few years.

I’ve written about this in more depth elsewhere, but basically what happens in it is this: in many books with two storylines, one is shorter than the other, and the short one usually terminates at the two-thirds mark of the book or right before the beginning of move to the finale—or at the “break into act three” point of the Snyder formula above. Successfully pulling this off creates that feeling of “everything coming together in the end” that makes these braided narratives so satisfying.

If your novel draft has multiple storylines—or you think you might want to restructure it to have them in the next draft—label each of your storylines with a letter, then try to break them into alternating numbered chunks of equal size, maybe ten or fifteen pages at a time, or whatever you think your optimal chapter length is.

You might end up with something like this, the structure of Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice:

A1, B1, A2, B2, A3, B3, A4, B4, A5, B5, A6, B6, A7, B7, A8, B8, A9, A10, A11, A12, A13, A14, A15

Or the structure of Alix E. Harrow’s The Ten Thousand Doors of January:

J1, J2, T1, T2, J3, T3, J4, T4, J5, T5, J6, T6, J7, T7, J8, J9, J10, J11, J12, J13, Epilogue

Or N.K. Jemisin’s triple storyline in The Fifth Season:

Prologue, E1, D1, E2, S1, E3, D2, E4, S2, Interlude, S3, E5, D3, S4, E6, S5, E7, S6, D4, E8, S7, Interlude, S8, E9, S9, E10

What you’ll probably discover, as you do this, is that you’ll need to revise and rewrite chapters from one storyline to make them proportional to the others, if they’re going to braid correctly. For instance, you likely can’t have a 30-page opening in one storyline and a three-page opener in the second, unless you’re going to keep up that balance the whole time. The pressure of trying to braid your storylines will be frustrating, probably, but also productive: it’ll help you see where in each storyline you need to do more work, setting you up for clear next steps to take in your rewrite.

The Nested Narrative

A variant on braided storylines is the nested narrative, which I’ve really only seen in David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas and Lance Olsen’s Calendar of Regrets. In the Mitchell, it goes something like this, with five of its six storylines arrayed to either side of the central sixth:

A1, B1, C1, D1, E1, F, E2, D2, C2, B2, A2

Very few books are going to work like this! But it’s at least one more example of how the material of multiple storylines might be successfully arranged. I’m sure there are many more!

The Serial or Episodic or Picaresque Plot

In a picaresque or a serial plot, the story does not so much steeply escalate as continue, often along a predetermined route: for this to work, there may need to be a clear beginning position and a clear ending goal, which creates a path upon which a potentially unlimited number of episodes or narrative waystations might be placed.

A road trip novel, for instance, begins in one defined place and (usually) ends in another that’s known almost from the beginning. (Or at a true destination that’s only discovered once the false destination is reached.) In a three-act novel of this sort, the first act might be the event that gets the characters moving, the second act is everything that happens during the road trip that is the protagonist’s proactive reaction to the inciting incident, and the third act is what happens once they arrive at the destination: more often than not, the second act of this sort of a novel is disproportionately larger than the other two.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is a classic serial/episodic narrative. The Road is a contemporary one. The raft carries Jim and Huck down the Mississippi River; whenever they step off it, story happens. In The Road, the father and son need to get south, where they might find warmer weather in their post-nuclear world; the story is the series of encounters they have in which the father slowly sacrifices his morality to protect his son’s innocence.

Note that while the serial novel can be continued indefinitely by inserting more episodes, delaying the final destination for too long may eventually derange your characters: the sitcom How I Met Your Mother, for instance, eventually undermined my sympathy for its lovelorn protagonist Ted as the show stretched into nine seasons; the HBO anthology series Love Life tells a similar story in ten episodes per protagonist, creating a more natural progression out of the various tropes of the marriage plot and the rom-com.

Freytag’s Pyramid

Maybe only because so many of us were taught Freytag’s Pyramid first thing in our creative writing education, it sometimes gets spoken of in disparaging terms—I think students worry it’s “old-fashioned” or “formulaic”—but the truth is that many, many stories and novels follow it to great success. This way of conceptualizing narrative has lasted because it works, and it might work for you and your novel too.

As a refresher, the basic stages of Freytag’s Pyramid are: exposition, inciting incident, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution, and denouement. (Here’s a quick explainer, if you’d like more detail.) One thing to note is how much more flexible this structure is than the others above, despite Freytag’s reputation as a rigid formula: there’s a lot of room to play with inside each of these stages. (The rising action especially can go on a long time, as long as it continues to escalate and complicate: it’s the part of Freytag that’s most like the serial.)

As with the other models above, map the material of your first draft against Freytag’s Pyramid and see how it fits. (I know I said this above, but it’s important to repeat it here, for a reason that’ll be apparent in a second: map only the action of the time narrated, the primary timeline of the novel.) What’s missing? What’s misshapen? What needs to be moved or compressed or expanded?

One note here: pay a lot of attention to where the inciting incident is located, because most of the causal propulsion of Freytag’s Pyramid emerges from that moment. Note especially that, most of the time, the inciting incident cannot occur in backstory. I’m sure there are exceptions, but usually it must happen on the page, where the reader can see it, in the time narrated of the novel. If you map the primary timeline of your novel and the inciting incident is off your chart, then it’s likely that you’ll need to adjust that.

Your exercise

The next time you complete a first draft of a novel (or story or narrative essay), create a beat sheet of the events in the primary storyline, then map the events against one of the structures above, or another of your choosing. The places where your first draft doesn’t fit the map will suggest some of the structural revision necessary in the second draft: new scenes to write, storylines to add, places where you need to speed up or slow down, expand and contract. Revise your outline until it better fits your ideal structure, detailing the better plotted version of the novel to come.

Once you have this new map in hand, you’re ready to begin the next draft. Now all that remains is to write it—and if you want suggestions on how best to do that, you’ll find them in Refuse to Be Done.

Good luck! See you next month!

Thanks so much for reading! If you’re not already subscribed, please consider doing so by clicking the button below. This post is also publicly accessible, so feel free to share!

Matt Bell’s novel Appleseed was published by Custom House in July 2021. His craft book Refuse to Be Done, a guide to novel writing, rewriting, & revision, is out now from Soho Press. He’s also the author of the novels Scrapper and In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods, as well as the short story collection A Tree or a Person or a Wall, a non-fiction book about the classic video game Baldur’s Gate II, and several other titles. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Esquire, Tin House, Conjunctions, Fairy Tale Review, American Short Fiction, and many other publications. A native of Michigan, he teaches creative writing at Arizona State University.

I heard about your book on a podcast a couple of weeks ago and am currently devouring it while in revisions. RTBD is saving my sanity and keeping me going. It's just brilliant. Thank you.

Happy launch month! I so enjoyed your talk last night at Porter Square Books in Boston at the new GrubStreet space.