#53: Traveling for Research: A Field Report

Jack Hitt, Andrew McCarthy, The Codex Calixtinus, Tom Bissell, John Kelly, James Salter

Hello friends,

Late last night, I returned to Phoenix after a month of researching and hiking and researching-while-hiking in Europe, a trip that ended in a two-day travel experience that included a transatlantic flight that turned back to London halfway across the ocean due to engine trouble. (My backpack is still in the UK… somewhere.) But all’s well that ends well, and I’m happy to be home and sitting at my own desk, writing to you again.

In June, I wrote a newsletter on the research methods I’ve accrued over the years, and this month I thought I’d follow that up with some reflections on what worked for me on this trip. For context, I’ve been working for a little more than a year on a novel based partly on medieval practices of pilgrimage and penance (among other things), which led to me deciding to walk the Primitivo route of the Camino de Santiago across Spain, starting in Oviedo and ending about 200 miles away in Santiago de Compostela. (My novel isn’t about this particular pilgrimage, but its context has some useful-to-me analogues that made it a good choice for my research.) I walked the pilgrimage solo, then met my girlfriend in the Alps to walk the Tour du Mont Blanc route through France, Italy, and Switzerland, which covered another 115 miles or so of much tougher terrain. I carried a 25-pound backpack every day, wore the same two or three outfits nonstop for a month, and slept primarily in alburgue dorms (on the Camino) and in various refuges, refugios, and hostels (in the Alps), with occasional private rooms sprinkled in as a break from communal living.

Both treks were fantastic experiences, each better than I expected but in different ways, and I’ve returned home with a new outline for my novel, tons of new details to fuel scenes and dialogues, in addition to my personal experience of pilgrimage and long-distance travel on foot. I have no doubt that I’ll write a better book for having taking this trip, and I can’t wait to get back to work on it. (Tomorrow!) Here’s some of what I learned during my month of research-driven travel:

Do Advance Research So It Pays Off in the Field

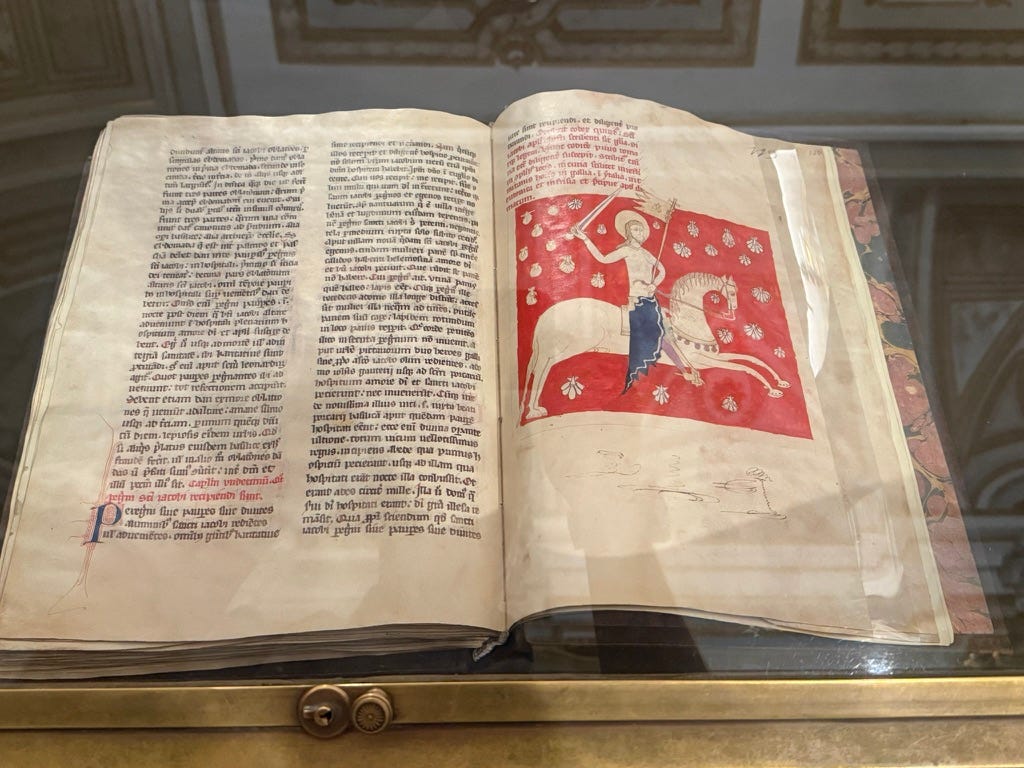

I’ve been researching various topics related to my novel-in-progress for over a year, generally following my nose but also taking the occasional assists from friends and colleagues who work in related fields. (One of the great joys of working at a good university is being surrounded by experts who are generally glad to share their deep wells of specialized knowledge for the low price of a cup of a coffee or a couple beers.) But in the weeks before leaving for Spain, I read a handful of books specific to the Camino de Santiago or the things I thought I might see along the way: among other things, I read two English-language Camino memoirs—Off the Road by Jack Hitt (which provided some of the events dramatized in Emilio Estevez’s Camino film, The Way) and Andrew McCarthy’s more contemporary account, Walking with Sam. (I tried to read Paolo Coehlo’s The Pilgrimage, but, well, could not.) I read a translation of the Codex Calixtinus, a 12th-century French guide to the Camino, as well as a scholarly treatise on it—later I saw the manuscript in the Cathedral de Santiago, after the end of my pilgrimage. I read Tom Bissell’s excellent Apostle, which offers a lot of early Christian history to support a travelogue of Bissell’s visits to the supposed tombs of the twelve apostles, including that of St. James in Santiago de Compostela, the destination of my own journey. And I read an academic history of St. James as he appears in history, art, and culture, which provided a lot of broader historical context for the region I was about to walk across.

Once I arrived in Spain, my reading paid off in numerous ways. Having grown up a studious, devoted Catholic—and having just refreshed myself on a good amount of early Christian history and art—I was often able to recognize the symbols or retell the stories embedded in many of the Christian sites, art, and architecture I came across, a constant experience on the Camino Primitivo route I walked.

Most memorable might be the rest day I spent wandering the Cathedral de Lugo and its resident museum, where (with the wise help of a new friend and fellow pilgrim), I was often able to “read” the art, statues, and various relics, unpacking stories and symbols that I might not have been able to decipher even a month earlier. The museum signs were in Spanish, the saints and other characters went by different localized names than they do in English, but the research had prepared me well to figure out who was who and to make educated guesses about the meaning of various arrangements. Even better, being able to see better made me want to see more, turning my attention up and my pace down. I loved trawling my way through each chamber, slowly picking out details I might’ve passed by without a thought, if I hadn’t done my research, if my research didn’t allow new details I was learning in real-time to constellate with what was already in my head. Much of what I saw was interesting enough on its own, offering some small intellectual or aesthetic reward for my having done the work—but some of it was revelatory, directly feeding my new conception of the book I’m writing. Day after day, my understanding of my book’s world (and my characters’ inner lives) was steadily improved by what the at-home research let me experience once I was on my own pilgrim’s path.

Cultivate Attention (by Removing Distractions)

Before leaving home, I did some radical surgery on my iPhone’s long-settled home screen: I deleted Instagram and Bluesky, my only social media apps; I moved the NYT app to a folder on another page, so I couldn’t easily click on it; I deleted or signed out of all of my streaming video apps and otherwise got rid of all the ways I generally distract myself. In their place I added a handful of Camino-specific apps, two of which turned out to be invaluable (Buen Camino and Camino Ninja, the first for its map and the second for its excellent stage-by-stage breakdown of places to eat and sleep), as well as WhatsApp and Booking, neither of which I’d used before but turned out to be vital for making arrangements with alburgue hosts and other pilgrims I’d met along the way.

So far so good! But once I started walking, I resolved to keep my mind as free as possible. During my 21 days of trekking, I never logged into social media or any of my other feeds; I read only the headlines of the NYT once a day (a tough withdrawal for a news/politics junkie like me), wanting to know what was happening but not wanting the actual texts of the articles in my brain; I listened to no music, no audiobooks, no podcasts, did not put my earbuds in while on the trail. (I did sometimes use them to block snorers in the dorms.) I watched zero streaming videos, no TV, no movies. With two memorably good exceptions—a hot afternoon spent with one fellow pilgrim and a long rainy day haul with another—I walked my pilgrimage alone, completing something like 185 of my 205 miles solo.

Without exaggeration, I can honestly say my generally busy brain had never before been so empty, at least since the advent of the internet and the cell phone.

What did I do with all this loose attention? I walked and I looked and I listened and I thought and thought and thought, without anything else for my mind to fix on. I followed the ample signposts and yellow arrows pointing the way along the Camino. I watched the roadside sights and sounds of the many miles of Asturias and Gallicia I passed through. I practiced my (very poor) Spanish, puzzling out signs and saying hello to the locals I met. I took hundreds and hundreds of photos. I pondered the many churches and shrines I passed, thinking through the particulars of their altarpieces, following the unique sounds of their bells, reading the site-specific prayers posted on their doors. I thought hard about my life, which has changed so much this past year: When I decided to walk the Camino over a year ago, I didn’t know I was going to get divorced or that my dad was going to pass away before I left.

So I walked and I thought and I also worked constantly on my book, mostly in my mind but also jotting down notes in my phone as I went. (More on journaling and note-taking in a minute.) As I said above, the book I’m writing isn’t about this particular pilgrimage or this particular landscape, but it was so valuable to be on a similar journey of my own, living a version of the daily experience of my protagonist. With nothing else to distract me, my book remained close, sometimes even seeming to look out from behind my eyes: it knew better than I what it wanted to see, what it needed to look at, and I did my best to carry it wherever it wanted to go.

Related—but certainly not a coincidence—the best writing-while-walking days I had were the foggy ones: one while hiking across the mountainous Hospitales route, another on a soupy, humid morning spent moving village to village after walking out of the city of Lugo. With less to look at, my mind turned further inward, turning over the pieces of my novel while I peered through the fog for the next guidepost, often just a couple steps out of sight through the mist. On one hand, I’m said I didn’t see more of the views I might otherwise have, especially in the high terrain of the Hospitales path—but I’m so glad I got to see the inner landscape of my novel all the more clearly for having missed some real-world vistas.

Journal When Time Permits but Note Ideas as They Arrive (Or Risk Losing Them)

Part of a long-distance, multi-day backpack trip like the Camino de Santiago or the Tour du Mont Blanc are what you might call “camp chores,” all the little jobs that have to be completed once you finish each day’s hike. On the Camino, this might mean finding a place to sleep (if you don’t book in advance, as I didn’t for part of my trip), then, once settled, taking a shower and changing into the clothes I’d wear the rest of the evening, sleep in, and then hike in the next day. Then I’d handwash the clothes I’d just taken off, hanging them to dry before heading out for food, drink, groceries, and whatever else I needed for the next day.

Inevitably, I would eventually end up in a street cafe, drinking a coffee or a beer and doing my journaling, getting down the personal experience of my travels as well as ideas and new prose for the novel. I did my best to get this journaling done every day, and to never hurry the task. I knew so much new stuff would happen every day that it would be impossible to remember it all without aid. But of course my journal lived in my pack, which meant I wasn’t going to get it out every time I had an idea or saw something I wanted to remember. So I also kept two documents in my phone’s Notes app, one for personal reflections and one for the novel. Some of the most important revelations I had got captured there first, and I fully believe much of what I discovered might have been lost if I hadn’t found a way to get them down right then. (Also, once written down they can be reread—and the reading can prompt new ideas. It’s harder for two ideas to build on each other in the mind, or at least in my mind.)

No matter how far I had left to walk for the day, no matter how bad the weather was or how treacherous the terrain, I always stopped to record a good idea. Wasn’t that why I was there? I never assumed a good thing would come around again. After all, everything about the particular place and time that prompted it was already falling behind me, step by step, and who’s to say if I’ll ever pass that way again?

Read Books Set Where You Are

One reason to read is to visit places you might never see with your own eyes. I’ve been traveling this way from my earliest days as a reader, when New York City was just as far away and unlikely a place as Middle-Earth. But eventually, I did get to go to New York, at least—I suppose the Shire will have to wait—and when I did it was in some ways like visiting a dream I’d had, because so many of the street names or Subway lines or buildings were places I had already been, if only in my imagination.

I’ve already mentioned above my prep reading, but while in Europe I also read from books set in or related to the countries I visited. The French epic The Song of Roland had come up in my research, for instance, so I read some of that while traveling, as well as the related Italian epic Orlando Furioso. I read a fantastic Europe-spanning history of The Black Death (John Kelly’s The Great Mortality) throughout my travels—and after the Tour du Mont Blanc I arrived back in Geneva at the exact moment the plague arrived there in my reading.

The best, though, was rereading James Salter’s novel Solo Faces, the book that years ago introduced me to Chamonix in France, where my Tour du Mont Blanc began. Salter’s book is about mountain climbing, not hiking, but it’s what first made me want to visit there, and rereading his story set in the same part of the Alps I’d be crossing was a blast. On the bus from Geneva, I got my first starling glimpse of Mont Blanc just as Rand arrives to the same, coming from the United States; I woke early the morning we started our trek to read and watch the sunrise through the balcony door of my rented apartment, following Rand out of Chamonix and into the mountains while my girlfriend slept beside me. Wouldn’t we be walking out soon too, right behind him? On the last day of our tour, I was drinking a beer in a refuge when I recognized the peak of the Dru (Les Drus, according to the French language placemat that helped me sight it…), an important location in the novel. I pulled up my ebook copy of Solo Faces and read aloud my favorite part of Rand’s Dru climb while toasting the peak, its prominence slowly being swallowed by the clouds as I read. A truly magical moment.

A good book should probably be good wherever it’s read. But there really is something great about reading a good tale in its own setting, with the same sights and sounds and smells surrounding you that surround the protagonist, bonding you together in the senses as well as story.

Open Yourself to Others

Before I left home, I told myself a little story: “It’s okay if I don’t meet or befriend anyone while I travel. I’m there to research, not to make friends.” Of course, this was mostly self-protection against something that could’ve felt like the first day of summer camp or starting a new school: What if no one likes me?

Thankfully, I did meet plenty of interesting, intriguing, and kind people both among my fellow pilgrims and trekkers and among the locals along both routes. As much I enjoyed the extensive solo portions of my travels, there’s plenty that I wouldn’t have seen or taken note of without talking to others every evening. Everyone carries with them their own particular attentions and areas of knowledge, and as useful as it was think on my own, it was also a pleasure to get to think in dialogue and to learn more by listening. My experience wouldn’t have been as rich without the presence of the people I traveled alongside, and I’m grateful to everyone who shared a trail or a meal or a dormitory bunkroom with me. (Along the Camino, most pilgrims walked the stages at the same daily pace, so you saw the same people over and over, forming friendships and helping each other out as you went. A really special experience!)

Specific to my writing, my own move from traveling alone to traveling as part of an ad hoc group made me reflect on the general loner tendencies of many of my protagonists, including the one in my novel-in-progress. One way or another, I realized, part of this protagonist’s journey has to be toward community, as part of my own journey has been, not just this past month but throughout my adult life. Seeing this helped fix a plot problem in my third act, and the solution I came up with already makes the book’s thematic material feel like it might now be more richly realized.

Grow Your Capacity for Effort with Effort

I went into what I knew would be a physically demanding research trip—14 days of hiking in Spain, 8 days in the Alps, 10-20 miles per day—dragging an overuse injury from running in my left foot, an injured elbow in my left arm (hurt by bowling with small children, of all things), and a sore right shoulder. Essentially, I arrived in Spain with one fully working limb, knowing I’d need to haul everything I’d brought on my back for many miles every day. To be honest, I wasn’t entirely sure I’d be up to it. But I had with me my hard-earned physical and mental base as a long-distance runner and a hiker, and of course there are also the habits of a novelist, which include sustaining perseverance in the face of uncertainty.

You might expect such a trip to slowly grind down the body and the mind but if anything I found the opposite happening. Every day I got a little stronger, every day the pack felt a little lighter or at least easier to carry. If in the first days of the Camino, I started feeling a little worked around ten miles, that spot was soon at eleven miles, then eleven and a half, then twelve. It was a lot like returning to writing after a long time away from the desk: 500 words feels exhausting for a while, but then one day you run out of gas at 750 instead. Then 1000. Or maybe it’s still only 500 words but the sentences come out so much stronger than they used to arrive.

The body always eventually adjusts to the tasks it’s given. So does the mind.

The Alps had dramatically more challenging terrain than I’d encountered in Spain: After the first day of climbing out of Chamonix and then back down into Les Houches, my legs were trashed. They stayed sore for days—every step sore, in my quads and my calves—but we didn’t stop to rest. We kept piling up the mileage, kept ascending and descending through big elevation change days. Halfway through, the soreness disappeared from our legs and never came back. The fifth and sixth days of the trek were the longest days but were also the days we felt the best, which wouldn’t have been true if we’d had to conquer those challenges first.

In my experience, writing novels often goes like this too. With consistent effort, what was impossible at the beginning becomes the default by the middle; what was unsolvable in the middle gives up its mysteries just before the end, when you’re ready. I am the best writer I can be only very late in a book, once I’ve gotten a lot of practice writing it. In many ways, I became the person who could complete my pilgrimage or could circle Mont Blanc through the Alps only at the moment I did so—exactly as the only day I’m the person who can finish my novel is the day I finish it.

A Final Note

I finished my Camino by arriving at the Cathedral de Santiago on June 30, just after sunrise after hiking through the night. (Due to a historic heat wave, I actually hiked all night both of my last two days of the Camino, including a 20-mile segment I started at 1am and finished on no more rest than a 15-minute nap in a lounge chair outside a closed bar…) One by one, the closest friends I’d made on the Camino arrived after me, creating an ever more celebratory atmosphere as we cheered each other’s accomplishment. That day and most of the next, I hung out with my new friends, did some sightseeing, and generally rested after a couple hard nights. But I also knew I wanted to get some writing done, so eventually I separated myself from the others and went off alone to work.

Sitting in a street cafe, I ordered a beer and then another and while I drank I wrote most of a new novel outline by hand, pulling together everything I’d thought and felt and learned during the past two weeks. The next morning, I sat at the tiny desk in the attic room of my hostel and finished the outline, arriving at the end of a new understanding of my book just before I had to leave for the airport and fly to Geneva. It was a magical moment, full of the Big-R Romance of the imagined life of being a writer, and I’m so grateful I got to experience it.

I’m very aware of the immense privilege and the considerable expense of being able to travel and write this way: I’ve been a published writer for for over twenty years and this is the first time I’ve ever been able to put something like this together. I don’t take the experience lightly. I’m so glad I seem to have gotten so much out of it. Now that I’m home, I’m excited to get down to the real work ahead. One step at a time. One page at a time. For as long as it takes. With the greatest gratitude I can muster.

Thanks so much for reading! If you’re not already subscribed, please consider doing so by clicking the button below.

Matt Bell’s novel Appleseed (a New York Times Notable book) was published by HarperCollins in July 2021. His craft book Refuse to Be Done, a guide to novel writing, rewriting, & revision, is out now from Soho Press. He’s also the author of the novels Scrapper and In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods, as well as the short story collection A Tree or a Person or a Wall, a non-fiction book about the classic video game Baldur’s Gate II, and several other titles. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Esquire, Tin House, Conjunctions, Fairy Tale Review, American Short Fiction, and many other publications. A native of Michigan, he teaches creative writing at Arizona State University.

This was so wonderful to read. I especially loved this simple, but oh-so-true sentence: "The body always eventually adjusts to the tasks it’s given. So does the mind."

What a deep dive! Thanks for sharing your various journeys!